The Exchange of Material Culture Among Rock Fans in Online Communities

By Andrea Baker

Published in Information, Communication & Society

(Communication and Information Technologies Section, ASA, Special Issue)

volume 15, Issue 4, 2012, pp. 519-536. DOI:10.1080/1369118X.2012.666258

ABSTRACT:

In online rock fan communities, fans regularly offer goods up for sale or trade and sometimes give them away. These objects constitute the material culture of the fans and reflect the values of the people in the online groups. Using data from participant observation of two fan groups and 101 interviews with members, this article identifies the main types of material goods exchanged including imports of concert recordings, tickets to shows, apparel and accessories, and fan and band artwork. In describing how the objects are transmitted from one fan to another, this article shows how the process of giving and receiving material culture can strengthen bonds between individuals by using the new technologies of the internet. Exchanging material culture first described online in internet communities adds to an understanding of the increasingly permeable boundaries between offline and online interactions.

INTRODUCTION

In the growing awareness of the permeability of online and offline worlds, researchers have begun to explore how people move between these two realms, and how that affects their communication, relationships and lifestyles, both online and offline (see, e.g. Sessions, 2010). In this article, rock fans trade, buy and sell, and give away objects of value to them. The description and analysis of which kinds of objects are passed back and forth and how that occurs will show that this material culture can potentially create close bonding, forming stronger ties than possible without digital media. The heritage of countercultural values of free exchange without obligation that has characterized internet communities from the start undergirds much of the trading, gifting, and even the selling of rare objects among online fans.

Using data derived from a larger project containing an exploratory online questionnaire, fan interviews, and participant observation of fan sites, this article articulates major kinds of objects or parts of material culture that are traded, and tells how these come to exist online before changing hands to people in face-to-face interaction.

The main research questions are:

•What are elements of the material culture of the rock fan communities,

how are they transferred, and what is their role in forming social bonds

and social support?

•How does the material culture and its transfer help to illuminate

knowledge about online/offline boundaries and mergers?

•How does the historical context of the counterculture inform the practices

of exchanging material culture online?

After detailing the methodology and explaining the core ideas of material culture, non-material culture and exchange processes online, this article draws on data about four major types of objects: bootleg or import recordings, tickets sought and bought for various shows, apparel and jewelry, and artwork and posters. Particular attention is paid to objects that first appear online, are asked for online, or that a fan procures offline and chooses to display online. The findings for each set of objects include the processes of identifying the objects and exchanging them.

The discussion addresses how the material culture reflects the non-material and countercultural values of Rolling Stones fans, how the material culture bolsters the status and bonding among fan group members, and how examples from the findings provide an understanding of the dynamics of exchange of objects from online to offline.

BACKGROUND: THE GIFT ECONOMY, MATERIAL CULTURE, AND BONDING ONLINE

‘Gift economy’ is an anthropological concept derived from people studying potlatches, where giving away objects without cost increases the statuses of families in Native American communities from the northwest U.S. Writers on the internet involved in creating and running online communities noticed the free exchange of ideas and information (Rheingold, 1987; Kollack, 1999), perhaps most notably in The WELL (Rheingold, 1993, n.d.).The WELL brought together artists, writers, reporters and computer technologists from the Bay Area before spreading out to include others. People could collaborate in cyberspace without regard for space and time (see Barbrook, 1998).

In his article on gift-giving and other modes of transfer online, Skågeby (2010) includes exchange of information, services and objects. Here the focus is on the part of the gift economy that pertains to objects or material goods and add the traditional buying, selling and trading to the pure giving, which occurs without the expectation of a direct reciprocity. Because the material culture reflects the non-material or values and norms of a culture (see Ogburn, 1922), people gain status for regular contributions to the community, making available valued artifacts for others to consume, whether paid for or not. Designing and reproducing graphics and texts for t-shirts of interest to Stones fans, for example, and offering them to Stones fans makes someone known to many people in a fan community. Unlike clothing, which is most often bought by the wearer, bootlegs or imports, as they are called, of concert recordings are often distributed at little to no cost to recipients.

Both as a community goal and a result of online interaction, bonding through sociability (Effrat, 1974; Hillary, 1982) is enhanced through the exchange of material culture. Of the purposes of online community, Preece (2000) has identified ‘sociability’ as a key purpose and process of online venues, while Calhoun (2002) says community members share feelings and desires as well as information. The goals of each online community are linked to identities of members, their relationships, and how they communicate (Baym, 1995; Katz & Rice et al, 2004). The exchange of objects may solidify bonds within the group. These objects that are bought, traded and gifted will likely reflect the values and norms of the particular culture, in this case, fans of a classic rock group. Because many of the fans come to know each other and communicate online, their mode of identifying and exchanging objects becomes more problematic than offline, and is a phenomenon to be examined in this article.

In this description and analysis of exchanges of material culture are focal points that are informed by data gathered from fans of two online fan communities. The research begins to answer the issue of the place of objects within online fan communities, and the processes by which these are exchanged. Objects exchanged according to countercultural principles may contribute to the main purposes of groups online, whether informational or supportive. The findings here will contribute to the understanding of how permeability of online and offline domains combine to facilitate the transfer of objects, ultimately tightening the bonds among members.

Following the methodology and a presentation of the findings about types of material culture and its exchange, a discussion will delve into further dimensions of the findings, concluding with questions raised for future research.

METHODOLOGY: RESEARCHING FANS AND THEIR ONLINE COMMUNITIES

The data are from a larger project (see Baker, 2009) examining fan identity, relationships and online community norms. The research methods are informed by Anderson’s concept of researcher as member (2006), and the use of ‘virtual ethnography’ (Hine, 2000) to study online communities. Three components formed the qualitative methodology: an exploratory questionnaire, interviews with online fans and participant/observation of fan communities. The questionnaire was designed to introduce fans to the project and to gather data on subjects that might evoke further explanation in the interviews conducted later on. The forty questions on it were posted a few at a time and were constructed to elicit such information as how fans became interested in the band, how they discovered the fan board, and which Rolling Stone was their favorite. The two questions most related to material culture asked what kinds of memorabilia they owned, and about their favorite fan-related apparel. People could choose which questions they wanted to answer, and the median number of responses for the whole was thirty-five. A few people wrote to say they might wish to do interviews, rather than post answers identified by their usernames to the community.

Using volunteers, or fans selected by the interviewer to represent diversity, the researcher conducted the interviews privately by phone. A set of open-ended questions allowed the respondent to talk at length about matters brought up in the questionnaire, plus their concert experiences and other areas. Most related to this article, fans answered a question on what kind of objects they collected, mentioning those discussed in the findings. From the questionnaire and the interview arose the idea for examining the material culture in more systematic detail. More than two-thirds of the 101 fans interviewed come from ‘Shattered’, a large online community whose leaders are in the U.S. where the questionnaire was posted. Others who completed interviews came from 'You Got Me Rocking', a discussion board run by a person from Europe, TE, and from other fan groups online. More than two-thirds of interviewed fans are male, and four-fifths are from the U.S, with the same percentage in their forties and fifties, within an age range from 20 to 67. The semi-structured interviews lasted for an average of an hour and fifteen minutes, as short as thirty-five minutes and as long as five and one half hours.

The researcher joined the two fan groups as a member, and after about a year, in 2007, decided to research the community norms, relationships and identities of members, reading the boards of both groups daily. The discussion boards of the two communities periodically contained items with pictures and conversations about recordings, tickets, apparel and accessories, and artwork. Fans posting in these topics offer objects for sale, ask where to find particular objects, and display objects from their collections. Focus here is on how objects transcend the boundaries, whether stable or more permeable, between the offline and online world through processes of exchange.

FINDINGS: THE CONTENT AND PROCESS OF EXCHANGE OF OBJECTS

Types of Material Culture and Their Exchange

Before discussing implications of objects online for bonding within communities, this article discusses the main forms of material culture are and how these are exchanged. The music fans discuss the following main types of objects and illustrate how people discover their availability.

I observed online and offline activity for three years before concluding that the material culture of the fans falls into a few major categories. They were the items sought by fans and offered to them by other fans. The official fan club store had sold some of the items, but none were currently available. Pieces of material culture often become more valuable with age, as they are harder to obtain. Other pieces are of limited addition or one-of-a-kind. They are also apt to disappear over time.

The four areas of objects or parts of the material culture of Rolling Stones fans online include: (1) bootlegs or import recordings of Stones music, (2) concert tickets to shows, (3) apparel and accessories such as jewelry, and (4) artwork, including mass-produced and hand-made products. While covering the main sorts of goods bought and sold, traded, and given away, this typology is not exhaustive.

The relationship of e-bay to all of these is important, because while e-bay is one mechanism fostering exchange for all four categories of objects, in bypassing e-bay, a fan offers the objects to dedicated friends, acquaintances, or cohorts on the fan boards. While much gifting or selling to friends undoubtedly occurs through back-channel communications in email or private messaging, the online communities are repositories for exchanges in the space between completely public and completely private. Posts detailing available items are directed to members, often with directions to private message or email them if they want to express interest. People can read at each discussion board without joining, but without registration of a username, no one can post there or send a message to another member.

To compare the two Stones fan boards observed, Shattered and You Got Me Rocking, You Got Me Rocking has two separate forums outside of the general discussion to exchange tickets or recordings and miscellaneous items. These are called ‘Buy, Sell, Trade’ and ‘Ticket Trader’. On Shattered, fans check separate topics for members’ goods for sale and for those at other sites, especially rollingstones.com. For imports of concert tapes, they can go to the ‘spread the music’ topic, where people set up a system to distribute single or multiple copies of the imports.

For each type of object, transactions are noted which involve movement from online communities to offline social circles or interpersonal relationships. By tracing the process from display and description of objects by those offering them, to the choice and procurement of objects by receivers, the pathways between the domains of online and offline become clearer.

(a.) Fan Objects: Recordings and the Their Exchange

Though a full accounting of how music is exchanged is beyond the scope here, music is a primary medium of interest for the rock fans. Fans try to obtain recordings and videos that are not readily available commercially. In fact, the Stones boards have a policy that disallows the selling of commercial music. Most of the musical currency is from fan recordings or soundboard tapes of live shows, while outtakes of official recording sessions are also exchanged. Fans use audio and video devices to tape shows, sneaking past the security personnel who prohibit the larger recorders. Audiotapes from soundboards often marked ‘SDB’ are of superior quality to those from individual fans because they are professionally mixed for the acoustics of the room, and there is little noise from the audience. Somehow procuring access, fans give away or sell SDB tapes. With the fan tapes, the listener has a feel for the concert experience, hearing exactly the same sounds as the fan recording in that particular spot.

Methods of free access include downloading from places online that provide for people to share what they have, such as torrents.com. At Shattered, much music is recorded by hand, and then sent out through snail mail through a system called ‘Trees’. Whoever owns the desired music or that person’s designated recorder copies and sends it to ‘Branches’, or volunteers who are hubs within a geographical region. People sign up to be ‘Branches’ and ‘Leaves’, or those who receive the music from the Branches. No fee is required, although Leaves typically provide CD holders, envelopes, and postage to their Branches for mailing.

When the band is on tour, concerts considered good ones become particularly valued. After hearing a taping and for years after, people talk about its quality and content. While promoters discourage recording a concert on audio or videotape, people have succeeded in bringing recorders into concert venues. With today’s technology compacted into small video cameras and cell phones, fans more commonly record concerts. Phones with still cameras and video cameras are rarely if ever confiscated, either before entering or at a show. Fans at You Got Me Rocking have advised other would-be recorders to wait until the end of a show to snag a tape of a song, when security people do not care as much about rules. An area of conflict among fans occurs when people hold up their devices to take still and moving pictures throughout the show, blocking part of the view of others to the side and in back of them.

(b.) Fan Objects: Tickets for Concerts and Exchange of Tickets

Helping fans procure prime tickets for shows is a function of the fan boards, whenever the band is touring. The goal is usually to sit as close to the front of the stage as possible, without spending a fortune for tickets through scalpers. The large number of tips transmitted by fans for securing good seats not only increases satisfaction of fans with their fan boards, but also may contribute to greater attendance at concerts, according to data from interviews and observation. The hints may contain information unknowable without long experience. For example, fans provide clues on when to buy, advising that people may want to wait until the better seats show up on Ticketmaster, rather than panicking and ordering immediately after sales open. In some cities, choice tickets may become available on the day before or the day of the show, either online or through the box office.

Even more importantly, fans often have extra tickets, either by accident or intention. They give, trade, or sell these to each other, after first exploring networks of close friends and family members. Knowing that someone from another city may want to come in for the concert, fans build up points with each other by distributing hard-to-get tickets. Traveling companions from the same locales often buy for each other, when they can. Backstreet Girl talks of how she gave an extra ticket to a sought-after small theater show to someone she owed for a ticket she obtained from her for another concert. Here two fans discuss transactions for two different shows:

Fan #1: When you get 4th row seats at Phillips Arena because of a

fellow Shattered fan—Frank, you know who you are & I'll love you til

my dying day for that. ;-)

Fan #2: It's all Shattered payback Girl!

You had never met me but sent me four tickets to get 4 of my friends

that would otherwise not get to see the Durham show due to your

family emergency. It was the least I could do! Shattered Love! It is

a Great thing!

At an online fan group, a fan started a ‘buying circle’ to obtain tickets for an in-demand show at the theater where Martin Scorsese was filming the band for the concert documentary Shine a Light. People shared their credit card numbers with near-strangers to increase their chances to buy a seat when ticket selling opened. Only a few thousand tickets went on sale for seats for this two-night run at the Beacon Theater in New York City. A number of fans who won a contest sponsored by the official Stones website occupied some seats, along with those able to buy from the leftover ticket pool. The crowd for the second night of filming consisted mainly of hard-core fans that filled the available 2100 seats in the theater.

A fan expressed gratitude to someone in Shattered for allowing him to go to a small show in another country:

… you wire money from abroad to someone you've never

met for a theater-concert ticket; travel several thousand miles;

arrive a day and half earlier to queue in line to land first row

(because you know this is the dream of your life;) you are ninth

in line and you never doubt – (have) not the least of a hunch –

that you might be tricked, even when your connect is several

hours late.

…because of Shattered, you were able to stand right in

front of Keith to hear him play… (you) threw him a rastafari

scarf and high-fived him once.

He benefited from the trust among fans wanting to help each other after connecting online in their common interest.

Angie99 from You Got Me Rocking came up with an ingenious way to keep ticket prices ‘reasonable’ yet attain prime close-up seats for selected shows on the last tour. She would write to people selling a seat on ebay, to strangers who with an extra ticket, and tell them she would get there many hours early outside the venue to save a spot in line for wristbands. When the doors opened for the show, fans could enter in order of where they were in the queue. Sellers on e-bay would lower their price in exchange for a good chance at a place near the front of the audience. Angie99 went to four ‘club shows’ that way, at venues of much smaller sizes than stadiums and arenas.

(c.) Fan Objects: Apparel and Accessories and Their Exchange

Fans typically sell their fan club shirts online to members. The first Shattered shirts were a bright shade of lime green, often criticized for their aesthetics but praised for visibility to the band. Shattered’s leader StonesRick initiated the first edition and sold it online, taking orders in the discussion board, while another person took over subsequent runs in later years, even producing a blue version. Band members are perceived to recognize fans wearing Shattered t-shirts and Shattered wristbands, the blue rubber bracelets stamped with the Shattered logo, also sold online in the past. One fan snapped a photo of Ronnie Wood, Stones guitarist, reaching down to take a wristband offered by a Shattered member, Ruby_Tuesday. She was seated close enough for Ronnie to take it from her hand. He wore it then and on several future concert appearances. While in his Shattered shirt, another fan, JackFlash, encountered the Stones promoter who gave him and his spouse passes to the Rattlesnake Inn, a pre-show, behind the scenes space for selected visitors where band members or their back-ups occasionally drop in to chat or eat.

The leader of the online community You Got Me Rocking developed a fan club shirt by consulting artistically inclined fans. Its four-letter logo is prominently displayed over photos of each of the four main band members. Although they were only available for the last tour, fans claimed the band was beginning to become familiar with the shirts. Fans debated versions of the design online, ordered the shirts through email, and then those who missed the deadline pleaded with TE to make more. Fans wearing the You Got Me Rocking and the Shattered shirts can see who else shows up at concerts and related events who belongs to their online fan group, creating an instant bond or at least an introductory topic of conversation.

Fans sometimes decorate their own apparel or logo-embossed denim jackets and caps with Stones pins and badges. In this way, they personalize their clothing with mementos from their collection of symbols from each tour. One fan moving from a northern European country to Central America after retirement posted pictures of a jacket he was selling, along with other memorabilia. In 2008, it had numerous patches and badges or pins, including the pin with a woman riding a Stones tongue, the dragon patch on the sleeve, the panel of four Warhol-like split-color tongues from the Licks tour, and pins symbolizing two tours on each side of the collar. On the back is a huge red tongue with a black background. He sold it to a fan that wanted it for a present for her son. Fans appreciated the uniqueness of the garment, with all the emblems on the jacket, pre-collected from past tours and sewn on one by one.

Although much jewelry and apparel is available through rollingstones.com and e-bay, fans sometimes sell and distribute it or even make it and give it away. One fan from Shattered created bracelets spelling out individuals’ names out of plastic beads for people who posted they were attending a fan function. She announced their availablity online and then handed them out to women gathered to hear a cover band. People expressed their appreciation to her afterwards, face-to-face and later online. Another female fan took orders for custom-made charm bracelets and necklaces, with the choice of Stones’ pictures and the tongue logo for each charm, and distributed those at a similar gathering. Toward the beginning of the last tour, 'A Bigger Bang' in late 2005, Stoneschick99 found someone to make a strand of wooden beads (see Figure 1), alternating one and three quarter inch long wooden tongues with red and black round beads that both men and women could wear.

[INSERT FIGURE 1 ABOUT HERE]

She bought and sold them mainly online, giving them out at fan functions and also shipping them:

Ok, i am gonna edit the first post with the list of requests for

mail and delivery at Walters, prepaids and cod's, LOL. Pm or

email me if you are not on the list.

Most fans who ordered bought multiple sets at four dollars apiece plus two dollars for postage if mailed, and some expressed their gratitude online, such as here in this post:

YIPPEEE YAHOOO--Thank you Stoneschick99! I just got my

bag of gorgeous beads today! I'm so excited and grateful to

you for all of your diligence and efforts!!

Though heavy, some people continue to wear them years later, along with the lighter red and black strands of beads passed out by a male fan for free on the same tour. Both advertised their necklaces at Shattered. When asked for their favorite Stones-related possessions, a few people mentioned their beads from Stoneschick99, as well as their Shattered t-shirts discussed above.

(d.) Fan Objects: Artwork and Posters and Their Exchange

A few people in the online communities have artistic skills and practice their drawing, painting or photography using members of the Stones as subjects. Band member Ronnie Wood is noted for his paintings and prints of individuals in the band, and of the whole band practicing or performing together. Some fans collect his art, which is priced at one thousand dollars per work and higher. Sebastian Kruger, a German artist, does caricatures and portraits of famous figures including the Stones. One fan has developed a working relationship with these artists and sells their pieces directly to fans, at a better price than they would get from galleries.

A fan called a_shot_away made her own avatar of Mick Jagger, a black and white graphic of his face. Another fan created photo collages of tongues that he sent to people for free, and designed 3D pictures of band members offered to fans for a small fee. A recipient adopted one of his photos as her avatar for a time, stating how beautiful she thought his shot of Mick and Keith was. An artist who depicted Mick and Keith sold his works to fans at You Got Me Rocking. Others sell Stones posters from their collections as they attempt to reduce the number of items.

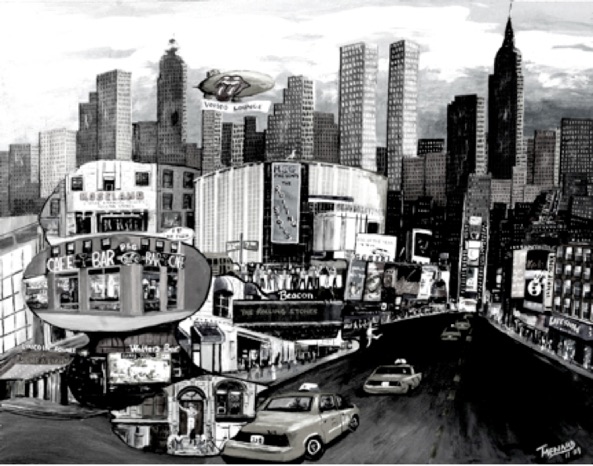

Within a few month time period, starting before Christmas, on Dec. 2, 2009, an artist who usually does commissioned pieces put up an artwork for sale. He sold fifty small prints, five large ones, and the original of this piece, related to The Rolling Stones and the fan group Shattered.

[INSERT FIGURE 2 ABOUT HERE]

This artwork entitled ‘All Over Manhattan’ depicts sites in New York City (see Figure 2) that have housed Stones-related events, primarily their concert venues, a movie theater, and a television studio. Painted in the sky is the blimp with the tongue logo that announced the Voodoo Lounge tour. It also includes the concrete steps on St. Marks Place well known to hard core fans where Mick Jagger, Peter Tosh and two others sat on location to film the video for the 1981 song ‘Waiting on a Friend.’ When Keith Richards arrives, he and Mick hug before departing together. The artwork features two bars commonly visited by fans before and after the shows, Walter’s, near Madison Square Garden, and the P & G Cafe. The artist describes some of the contents and the raison d’etre for the painting:

Letterman is there because of the Stones appearing on the Ed

Sullivan show… We met at the P&G because it was conveniently

located near the theater to see Shine a Light. I did the painting

as a Thank you to all my friends in the Babylon Lounge and

Shattered for all they have given me over the years through

laughter, tears, support and friendship.

People sometimes share their mementos of fandom online, whether album or CD covers, pictures or videos of shows they attended, or collected ticket stubs and artwork. Michael H posted the collage of objects he arranged on his bedroom bureau (see Figure 3).

[INSERT FIGURE 3 ABOUT HERE]

He has an artwork, a copy of an Annie Leibovitz photo of the four principals in the band, Charlie Watts, Ronnie Wood, Keith Richards, and Mick Jagger, ticket stubs from shows on the Licks tour of 2003, a fan club emblem, a CD from the Stones show in a small theater in Toronto, a skull ring like the one Keith Richards owns, and rose petals that Mick Jagger tossed into the crowd a to finish a show. Michael’s photo combines all four categories of material culture discussed here: imports, tickets, apparel and accessories, and artwork.

Going beyond the top of a dresser or table, many hard-core fans have dedicated a special corner, wall, or even a whole room to house their fan objects, a Stones ‘shrine’. An active member of Shattered since its start in 2001, MickeyRed described how her mother complained that her previous arrangement of mixing the Stones paraphernalia among her other things drove her mother crazy, how she ‘just put Stones stuff next to the designer home crap she bought for me…’ In her new residence, she and her husband ‘have a ton of stuff just waiting to set up the shrine in this old house, a room dedicated to only Stones stuff.’ When the shrine is ready for display to other fans, MickeyRed will hold ‘a shrine-opening party’.

DISCUSSION: MATERIAL AND NON-MATERIAL CULTURE, BONDING, AND ONLINE/OFFLINE WORLDS

The process of identifying, depicting and distributing material culture among fans occurs both online and offline. Objects exist offline and yet are embodied online in words and pictures. Prized possessions, new or old, singly or in groups, are introduced and shown online so that others can buy, trade or ask for them, or just appreciate their worth and the affection the owner has for them. Explored here are three aspects of the material culture of rock fans: (1) the relationship between the material and non-material culture, including the countercultural values, and the status-conferring power of material goods, (2) the role of material culture in fulfillment of the emotional and informational goals of online groups, and (3) how the processes of exchange of material objects link the online and offline worlds of fans.

The material culture described in the findings reflects the values of the non-material culture in that desired objects embody the fan’s attachment to the band, The Rolling Stones. People who display and exchange the objects thus demonstrate their allegiance visibly by owning and seeking to acquire the material culture or sharing these objects with other fans. The countercultural value of giving objects away rather than selling them for profit predated the free sharing of information online in the cyberculture (see e.g. Turner, 2005). The bestowing of objects onto others, or offering them as trades or for less money than they are economically worth is common in the rock fan communities.

Social capital accrues to people who provide resources, whether tangible or not. The concept arose to identify in particular the worth of nonmaterial exchanges, such as information. Here fans that provide information have status in the online community, and those who not only possess goods related to fan culture but who choose to share them acquire respect and affection. As noted above, fans can redistribute tickets to both friends and strangers, for money or not. A norm in the Stones fan culture is not to sell tickets for more than face value on the boards. Also, both boards prohibit selling of commercial releases.

Status or prestige on the Stones boards comes from a fan’s knowledge and resources and the frequency of posts the fan writes to acquaint other fans with what he or she knows or has. The amount and kind of material objects a fan possesses and displays builds respect among the readers. In general, the more a fan has, the higher the respect, with the intervening factor of the rarity of the object, and the degree of closeness to an insider status the object represents. Different objects receive more or less status, on a hierarchy of worth determined by fans. Objects given and signed by band members garner the most respect, as do the older objects, and those produced in low quantities. Fan status is displayed online when people thank others for giving, trading, or selling them an object. For the artwork ‘All Over Manhattan’ by Tomartstone, people weighed in with their appreciation on the Shattered discussion board both after the artist presented it for sale, and upon receiving it by mail. Public offerings also elicit private messages or emails of thanks.

Material culture can show how much a fan knows about the band and its history. For example, possession of a rare import or bootleg indicates that the fan perceives how important that particular concert is, either for its general quality or the rarity of the set list. Barring actual attendance, following the history of others' reactions lets the fan in on this bit of lore. Some mass-produced objects such as t-shirts or pins are readily available at the time of a tour or concerts, and become increasingly rare and more expensive over time, as people grab them up on e-bay or through fan boards. For example, a Valentine’s Day tongue pin from some years ago that sold for six dollars may bring fifty dollars today, if it can be found at all. Familiarity with the rarity of fan objects requires attention to available information and often, participation in real world events.

The material culture traded from online to offline and back illustrates both the providing of resources, and the bonding or social support within the community (see Marshall, 2007). Exchanging material culture binds people to each other, going beyond stranger-to-stranger transactions because of the fan interest in common. Even in buyer-seller transactions, fans sometimes become attached to a seller who specializes in particular goods and offers reasonable prices. Particular fans are known for their generosity in providing hard copies of rare CDs for free, or in uploading copies online for others to procure without cost or for a small fee to a downloading service.

Trading is sometimes offered, though fans may have trouble equating one piece or collection of music with another, or determining the comparable values of a garment and an import recording. An example of mass trading includes a gift exchange at a yearly gathering of Shattered fans at the end of the summer to hear tribute bands. The details of the exchange are announced online at Shattered before the event. Each person brings something to give away, and when his or her name is called, chooses from the pile of objects, old and new, ranging from t-shirts and belts to bumper stickers and posters, all with the band logo or name. People also trade music that is not commercially available. Some fans contribute more than one object and only take one thing, and a few donate but don’t take anything away, making the idea of the gift economy come alive by expecting nothing in return. The request for objects and music is made online by leaders of the community and carried out offline. People freely trade these fan objects of value, depending on personal taste and also their place in the randomly called list of names. Fans look forward to the exchange, selecting their contributions well before the event. They feel close to each other during the group exchange, and take their object home as a souvenir of the group celebration, a memento of the occasion, as well as a valued piece of fandom.

In the increasing fluidity between the online and offline worlds, members of fan groups naturally encompass this movement. Fans today buy music offline and online, of live concerts and recording sessions. When they can, they attend concerts offline and share their experiences there and online. The fans receive material goods through the mail or in person, after hearing about them most often online. Whether through impersonal sites like ebay and craigslist or the more personal fan groups, online venues have replaced much advertising in magazines and newspapers. In fan communities, personal bonds are both the cause and effect of exchange of material goods.

CONCLUSIONS

This section outlines future directions for research on fans and online communities. The themes for further research include the following: (1) a deeper examination of the crossover between cyberculture and counterculture, (2) the role of material culture in potential creation of greater bonding and social support among members, (3) how looking at material culture in various groups can increase knowledge about offline/online boundaries and mergers.

While many transactions of fans follow the usual patterns of the commercial world, some are outright gifts or notifications of objects of value to circles of fans online. The countercultural ethos opposed traditional norms of buying and selling with the giving away of material goods. The letting go of objects accomplished two goals, trimming down one’s own possessions to become freer of material attachments and sharing an abundance of riches with people who had less. This idea of spreading the wealth could conflict with another value common in members of both the mainstream society and the counterculture, individualism, epitomized during the 1970s by the saying ‘Do your own thing’. This dictum applied to taste in music, and clothes as well as other attitudes and behaviors.

One writer traces the tension in this self-other dichotomy from the ‘counterculture to cyberculture’, noting emerging if temporary solutions (Matei, 2005). As early as 1987, Rheingold wrote about the combination of altruism and self-interest that marked the habit of giving and asking for information online. He notes that for any question posed in an online or ‘virtual community’, multiple answers appear, while each person may forward relevant data to members whose interests coincide with a topic someone happens upon. The same balance seems to apply to material goods and services in the fan communities to reconcile conflicts between individualism and communalism.

A recent article reviews the literature on ‘gifting’, attempting to apply it to an online context (Skågeby, 2010). Skågeby looks at traditional vs. mediated gifting, focusing on the bonding potential of online gifting. He makes a case that social capital is more a property of individuals whereas gifting accrues to objects (p. 173). He concludes with the provocative notion that because of online openness to strangers, the bonding capability of objects in online venues is open to a wider distribution than in the close-knit, small family and friendship circles offline where gifting typically occurs. Conversely, perhaps the twining together of economic exchanges, trading, and free gifting found in the fan groups here contributes to a tightly knit online community of a kind analogous to long-term voluntary associations or clubs. These may replace or supplement the connections so mourned by Putnam (2000). More research is needed on the dynamics and outcomes of exchange in online communities to isolate the optimal comparisons with other groups and value systems.

Just as online relationships that start online can migrate offline, (see Baker, 2005; Tuszynski, 2008; Walther & Parks, 2002), objects can travel through textual description, pictures, and transferred ownership. Fans communicate in public discussion groups online and through private backchannels to announce, negotiate and distribute physical goods. The material culture reflects the norms, beliefs and values of the non-material culture, resulting in objects accruing value for their closeness to the target of the fan’s interest, in this case, The Rolling Stones band and its individual members. Further tracing the path of the material objects in different contexts from online to offline and back has promise in shedding light on the degree of ease or difficulty of crossing between online and offline worlds, as well as the motives of those who possess the objects.

From looking at pieces of material culture in the Stones world such as clothing, artwork, music and tickets that are sold and purchased, traded, or given away using online media, the processes of moving from online to offline and from offline to online are illuminated. The resulting transactions serve to strengthen the community purposes of sharing information and resources, and to connect the members, sometimes in intimate friendships that develop to pursue and enjoy fan activities. In current times of lesser offline community involvement, online fan communities with worldwide memberships may fill part of the gaps documented in declining participation in voluntary organizations. Indeed online communities likely foster more participation in what Stebbins (2007) has called ‘serious leisure’ pursuits of all kinds. To best examine the interplay between online and offline spheres of behavior, researchers will ideally continue to conduct their research in both realms to reflect the dissimilar as well as the common dimensions of interaction (Orgad, 2008).

REFERENCES

Anderson, L. (2006) ‘Analytic ethnography’, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 373-395.

Baker, A. (2009) 'Mick or Keith: Blended identity of online rock fans', Identity in the Information Society, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 7-21.

Baker, A. (2005) Double Click, Hampton Press, Cresskill, NJ.

Baym, N. (1995) ‘The Emergence of Community in Computer-mediated Communication’, in Communities in Cyberspace, ed. M. Smith & P. Kollock, Routledge, London, UK, pp. 138-163.

Barbrook, R. (1998) ‘The Hi-tech Gift Cconomy’, First Monday, vol. 3, no.12. Available http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/viewArticle/631/552 (8 February 2010).

Effrat, M. (1974). The Community, The Free Press, New York.

Hillery, G. (1982). A Research Odyssey, Transaction Publishers, Edison, NJ.

Hine, C. (2000) Virtual ethnography, Sage, Thousand Oaks.

Katz, J. Rice, R, Acord, S., Dasgupta, K. & K. David (2004) ‘Personal Mediated Communication and the Concept of Community in Theory and Practice’, in Communication and Community, Communication Yearbook 28, ed. P. Kalbfleisch, Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 315-371.

Kollock, P. (1999) ‘The Economies of Online Cooperation’, Communities in Cyberspace, ed. M. Smith and P. Kollock, Routledge, London, UK, pp. 220-239.

Marshall, J. (2007) Living on Cybermind. Peter Lang Publishing, New York.

Matei, S. (2005) ‘From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Virtual Community Discourse and the Dilemma of Modernity’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol.10, no. 3, article 14. Available at: http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol10/issue3/matei.html (10 August 2010).

Ogburn, W. (1922) Social Change, H.W.Huebsch, New York.

Orgad, S. (2008) ‘How Can Researchers Make Sense of the Issues Involved in Collecting and Interpreting Online and Offline Data?’, in Internet Inquiry, ed, A. Markham & N. Baym, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 33-53.

Preece, J. (2000) Online Communities: Designing Usability, Supporting Sociability, Wiley, Chichester, UK.

Putnam, R. (2000) Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, Simon and Schuster, New York.

Rheingold, H. (1987) ‘Virtual Communities - Exchanging Ideas Through Computer Bulletin Boards’, in Whole Earth Review, Winter, pp. 78-81.

Rheingold, H. (1993) ‘A Slice of My Life in My Virtual Community’, in High Noon on the Electronic Frontier, ed. by P. Ludlow, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 413-436.

Rheingold, H. L. (n.d.) ‘The Art of Online Hosting’, Available at: http://www.rheingold.com/texts/artonlinehost.html. (30 June 2010).

Skågeby, J. (2010) ‘Gift-giving as a conceptual framework: framing social behavior in online networks’, Journal of Information Technology, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 170-177.

Stebbins, R. (2007) ‘Serious Leisure: A Perspective for Our Time’, Transaction Books, New Brunswick, N. J.

Sessions, L. (2010) ‘How Offline Gatherings Affect Online Communities: When Virtual Community Members “Meetup”’, Information, Communication & Society, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 375-395.

Turner, F. (2005) ‘Where Counterculture Met the New Economy: The WELL and the Origins of Virtual Community’, Technology and Society, vol. 46, no. 3, pp. 485-512.

Tuszynski, S. (2008) IRL (In Real Life): Breaking Down the Binary between Online and Offline Social Interaction, Ph.D. dissertation, American Culture Studies, Bowling Green State University.

Walter, J. & Parks, M. (2002) ‘Cues Filtered Out, Cues Filtered In: Computer-mediated Communication and Relationships’, in Handbook of Interpersonal Communication, 3rd edition, ed. M. Knapp & J. Daly, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 529-563.

Figure 1. Wooden Tongue Beads

Figure 2. Tomartstone's 'All Over Manhattan' Art

Figure 3. Michael H's Collage of Objects