Down the Rabbit Hole:

The Role of Place in the Initiation and Development of Online Relationships (2008)

Down the Rabbit Hole:

The Role of Place in the Initiation and Development of Online Relationships (2008)

Down the Rabbit Hole: The Role of Place in the Initiation and Development of Online Relationships

In Azy Barak, Editor, Psychological Aspects of Cyberspace: Theory, Research, Applications. Cambridge University Press, 2008, pp. 163-184.

by Andrea Baker

When Lewis Carroll’s Alice falls down the hole into Wonderland, she encounters a variety of situations in various places: a garden, a forest, a pool, a kitchen, a castle and a courtroom, among others. The characters she meets who become her acquaintances, friends and enemies differ depending on her location in her travels, and, of course, her size. She follows the White Rabbit who is terrified of her larger-than-human height in the hallway. She learns to adjust her size to match the places, objects, animals and people who cross her pathways. People have likened “cyberspace” to the world found through the mirror, the virtual reality on the other side contrasted to the everyday physical world.

As the experience of people online accumulated, researchers differentiated modes of relating within cyberspace such as the use of the asynchronous and the synchronous or real-time media. They have begun to illuminate differences in the types of spaces, places, or settings online (see Baker, 2005, 2002; Baker & Whitty, 2007; McKenna, 2007; Whitty & Carr, 2006). A current line of inquiry attempts to explicate interactions that originate but do not remain in cyberspace, or relationships that span online and offline places. Researchers of online relationships recognize that people online often “felt as though they have gotten to know each other quite well” (Walther and Park, 2002 p. 549) before meeting offline (Baker, 1998), entering “mixed mode relationships” (Walther & Park, 2002). People develop strong feelings for each other in cyberspace, and forge relationships, from casual acquaintance to close friendships, and intimate partnerships sometimes leading to marriage (see for example, Baker, 1998, 2005; Ben Ze’ev, 2004, Cooper & Sportolari, 1997; Joinson, 2003; McKenna et al., 2002; McKenna & Bargh, 2000; Merkle & Richardson, 2000; Wallace, 1999; Whitty & Gavin, 2001). These connections first take place in a virtual world, without the two factors of physical attraction and spatial propinquity, dimensions previously thought essential for interpersonal bonding.

Taking off from the Alice’s adventures in new places, this chapter addresses two questions. First, and with primary emphasis here, (1) how does the particular online place or space in which a romantic pair meets influence the course of the relationship, especially in the early stages? Then, (2) how does timing, the pacing of the relationship by members of the couple, interact with space to affect the development of a potential couple pairing? Examining primary data and looking at the relevant literature on online dating, the chapter begins the exploratory analysis of how place relates to initial attraction and further commitment in romantic relationships in cyberspace.

Introduction to place and oniline relationships

People meet at various places online. The kind of meeting place indicates what kinds of people gather there, the commonalities they share, their first impressions, and the nature of their initial contact (see Baker, 1998, 2005). McKenna and Bargh described how sites in cyberspace contain different “gating” properties than physical space (2002), and have fewer barriers to interaction. Baker and Whitty (2007), and McKenna (2007) have recently noted that features of various types of online places produce multiple patterns in online relating. The kind of site or online meeting place provides different types of knowledge about the other and points to specific media for first person-to person contact, for example. “Place” here refers to the space where two people first encounter each other online, and then later on, if they choose to connect in physical space, the kind of place or location of their meeting offline.

An “online relationship” is defined as one where the two in the dyad first met online and are looking to each other for a romantic involvement. In beginning their relationships, the two may have consciously searched for intimate partners, or met online as friends or acquaintances and later developed romantic intentions. The data and literature come mainly from researchers studying intimate pairs, and individuals who are dating (or considering it), living together or married. Although personal relationships such as friendships can begin online, and even family relationships can occur mainly online, these are categories of dyads that deserve separate study, and thus, are mentioned only as they relate to the findings on intimate online relationships.

This paper discusses first, the issues of place or space online, and then the intersection of place and time in the formation and development of online relationships. Examining that combination, in particular, may open up new areas for research of relationships in cyberspace. In addition to citations from relevant studies, this chapter draws on the data from research on online couples by the author (see Baker, 2005) and later data collection with quotations taken from interviews conducted through phone and email and from questionnaires provided by pairs who met online. Individuals received pseudonyms upon entry into the research.

The ‘where’: Place in online relationships

In the discussion of “place”, this section first examines (a.) the distinction between online and offline places, the parameters of “cyberspace” (Gibson, 1984) versus “real life” places or locations. Included here is the concept of proximity or propinquity’s role in interpersonal attraction and how people approximate propinquity in cyberspace.

Moving into (b.) the types of places where people interact online, this chapter addresses the goals and dynamics of dating sites in contrast to virtual communities including discussion boards, games, social networking sites, and chat rooms. Finally, geographical distance (c.) between potential partners who meet online is examined, and how that distance affects the process of developing relationships online.

Place online and offline: Attraction in cyberspace vs. “in real life”

Cyberspace and offline reality share properties and they also differ in kinds of interaction within the two spheres. In the early days of internet research, researchers treated cyberspace as a pale reflection of “real life”, where people related through “low band width”. Areas comparing interactions in cyberspace to the offline world or “in real life” are first, physical attraction and propinquity, and then, common interests and their relation to the initiation of relationships in cyberspace.

Physical attraction and propinquity online

In cyberspace, the role of physical attraction is lesser than in physical space, depending upon the place. In the theories of attraction before widespread computer-mediated communication, appearance is, in many cases, the prime factor, if not the only one in how people become romantically intertwined (Berscheid & Walster, 1978; Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986), along with closeness in physical space or propinquity. Statistical studies of married couples affirm relative homogamy of age (see Fraboni, 2000; Wheeler & Gunter, 1987) and other demographic characteristics, and earlier research points to factors of attitude similarity and attractiveness in initiation of relationships (see, Bryne, et al, 1968). In contrast with the primacy of appearance, even in dating sites where photos are common, and where people sort through personal profiles partly on the basis of physical appearance, other factors such as place of residence, interests and style of writing can offset appearance. Older theories of attraction include propinquity or physical presence along with physical attraction. Propinquity or proximity online can mean closeness or co-location in cyberspace without nearness in physical space. If two people meet regularly at a discussion board, even if they post at different times, they grow to know each other, and expect their regular appearances, similar to offline neighbours or co-workers in contiguous offices.

Physical attraction and spatial proximity seem much less important in forming intimate relationships online, given the web (www) and email which link people from locations worldwide through the media of written communication (see Baker, 1998, 2005; Cooper & Sportolari, 1997; Fiore & Donath, 2005; McKenna & Bargh, 2000; Merkle & Richardson, 2000). Some people in relationships communicate by video or webcams, although almost no one from the author’s primary database did so, and none used video more than rarely. Even when presenting photographs or avatars, the process of becoming acquainted with someone begins in a virtual or non-physical plane, online, leaving the choice of whether or not to meet in person until later, after assessing what is known already through information provided online.

While Al Cooper coined the “Triple A” model of Accessibility, Affordability and Anonymity (Cooper, 1999) to address the popularity of sex in cyberspace, these three attributes help reveal the appeal of meeting people online for all kinds of intimate relationships. Without so much emphasis on physical appearance, cyberspace bonds often begin with mutual self-disclosure and rapport based on similarity of the individuals (see, e.g., Byrne et al., 1968; Duck & Craig, 1975; Pilkington & Lydon, 1997). The connections “stem from emotional intimacy rather than lustful attraction” (Cooper et al., 2000, p. 523). This is not to say that the dimension of physical attraction is unimportant. In its absence the couple will usually not continue the relationship. As one person in the research on couples (Baker, 2005) who met online described the process:

So, while I don't doubt that I fell in love before the meeting, I think the meeting

validated that. Let me use a really bad analogy: Online shopping. I can fill my

shopping cart and submit my credit card number. But if something goes wrong

after I hit "send," or I somehow forget to hit send, it's all pretty pointless. I've

purchased nothing (Rosa, interview through email).

Rosa had seen a picture of her future spouse, “a head shot” that she found unflattering, in comparison to the actual man. She spoke of how both she and her partner liked what they saw upon meeting in person.

On the internet, people can first get to know others, and then after that, decide if they want to meet them, rather than the other way around as in physical space (Rheingold, 1993, p.26). Attraction begins online, often through the written word or a combination of pictorial and textual representation instead of simply a physical presence. The “click” of felt compatibility comes through connecting in a place online and then communicating through text and frequently by voice before meeting face-to-face (f2f).

Common interests and similarity in cyberspace

Propinquity or proximity online means that two people have come to find themselves in the same area online, whether playing a game, discussing a television show they both watch, or sorting through profiles on a dating site. They have signalled a similar goal, whether to socialize, gather information or to seek entertainment. Depending on the type of site, they have often announced their availability for relationships, whether directly in a dating site ad, or more indirectly with references to spouses or significant others in a profile, or in conversation with people sharing the place.

Offline, if two people meet at a tractor pull, for example, they can assume certain mindsets and commonalities just by being there. The same thing holds online, for people who are in a group for those over 60, for example, who are discussing movies they’ve just seen. In a dating site, the availability is announced, a willingness to find at least some kind of relationship, from the serious to the more casual. The difference here with places online is that a large number of these are most often easier to access than offline, through the use of a browser and a search engine or through emailing people in the know.

A researcher (Wright, 2004) contrasted cyberspace and real life space when he looked at exclusively internet-based relationships (EIB’s) in comparison to primarily internet-based relationships (PIB’s). The EIB’s take place only on the internet, while the PIB’s contain people engaging both online and offline. Within the PIB’s, Wright did not separate out those who met online first, the “mixed mode” relationships (Walther & Park, 2002) that move offline from an online start. He states along with researchers such as Barnes (2003) and Baker (2005) that shared interests replace proximity online. Similarity of interests comes across perhaps more obviously online, says Wright, because the online communication through text in email or chat mutes other variables such as age and appearance.

The downplaying of age came up for one online couple when they met at an online dating site. Each chose age limits that excluded the other because their age difference exceeded fifteen years. Elliot saw a profile that attracted his interest in a list of the hundred most recent people to sign up for the site on its home page. He noticed a nickname, “Jordan” that he thought stood for Jordan Baker in the Fitzgerald novel The Great Gatsby. Actually his partner chose the name for a relative rather than for a fictional character liked by Elliot, but the couple had much in common, nonetheless:

I wrote her first, based on both her handle…and the text of her ad which

indicated a sense of humor (albeit a trifle warped -- something I like) and

a continuing interest in Theatre and Literature, two thing which are as

essential as oxygen to my life.

She replied with a brief "what you wrote was really interesting; I'm busy

now but will write more later" note; and she did; and, during the first few

exchanges, we discovered an astonishing confluence of unusual and

idiosyncratic commonalities, including the fact that about two weeks before

we began writing, she had visited a friend in Chicago who lived three blocks

from me and had, literally, walked past my apartment several times

(Elliot, questionnaire).

This couple had posted no photographs, although they exchanged them after beginning their email correspondence. They soon discovered a common fondness for the musical “Pippin” and for the poet Mary Oliver, and all the writings of J.D. Salinger. The two married a little over a year after meeting online.

Place online: Dating sites vs. online communities

Two major types of online places for people forming relationships include the online dating sites, and other places, such as discussion forums, chat rooms, email listservs, social networking sites, and games and virtual worlds. These kinds of sites other than the dating services are grouped together here and called online communities or virtual communities (VC’s). People visiting online dating sites have different goals, at least at first, than those at other sites. The sites also differ in how many people tend to establish offline relationships with each other. Finally the dynamics of forming relationships in the two types of sites are discussed.

Goals of online places and participants

Members of any particular online place enter with similar goals. People with common interests frequent the same types of online places or spaces, or urls, the website addresses, in a more technical sense. Within discussion groups, games, chat rooms, and dating services, the individual purposes or motives of participating members may vary, although each type of place has a manifest goal related to the type of activity or conversation found there. Thus, similar kinds of online places created for particular purposes, contain people with similar goals or reasons for being there.

The process of developing an online relationship, including the timing, discussed more below moves in various directions with different starting and of course end points, related to what the parties desire from the relationship. What the two people want will vary, on the whole, by the kind of site they visit.

Goals of people seeking intimacy online can range from desire for a casual encounter of either brief acquaintanceship or sexual contact (see for example, Whitty, this volume; Wysocki, 2007), to a commitment as deep as marriage or life-long partnership. Researchers examining members of a large dating site have identified other goals in between casual and serious intimate relationships, such as meeting a larger quantity of dating partners, becoming more experienced at dating, and finding friends online (Gibbs et al., 2006). They found that most people in their study of Match.com sought someone for a dating relationship of some kind. None of the partners’ initial goals precluded building a long-lasting, committed relationship.

In fact, some dating and married couples claim they were looking for friends or were actually friends first either in the course of interaction in a VC, or in the overt search for compatible others explored through online dating (Baker, 1998, 2005). A public television broadcast about “love” presented a woman about to marry her online partner telling the story of how they first met at a dating site: “Monica found Mark on-line by seeking friends and connections in her new area code. They met and liked each other immediately. They had a lot in common including their work as musicians” (Konner, 2006). The bride said that she and Mark had built a good friendship on the phone so that when she moved to Austin, she agreed to meet him for dinner. When he suggested they date, however, she hesitated, thinking “whoa”, that dating was step in another direction from their current relationship. She had entered the site with the thought of finding friends rather than a romantic bond.

Another women, a member of an online community told how she married an online friend. Her partner was “strictly a friend online” but they became romantically involved offline over a three-year period (Lethsa, quoted in Carter, 2006). Friendship is probably more commonly the goal at online communities than dating sites because people are driven to join by an interest in discussing particular topics or in playing games, or interacting with people they may enjoy. A participant in this author’s research, explains in an email that meeting in a VC “worked” for her:

… mainly because we were not in that community to meet a mate. We

were there because we were interested in the community first, to engage

in stimulating conversation, to challenge our bases of knowledge, and

share our opinions and experiences.

Presuming daters have a variety of goals or motives propelling them to sign up for dating services, two researchers suggest that one dating site alone may not fulfill all of them (Fiore & Donath, 2004). Site designers would have trouble meeting all of their users’ needs for different types of interactions. Even within the diversity of goals, most participants in a recent study of the Match.com dating site wanted to find a person for some kind of dating relationship (Gibbs et al., 2006), although with varying levels of commitment. An advantage of the dating site for couples is the explicitness of the goal of meeting a dating partner, whereas the VC’s do not generally filter out married people, those already in a relationship, or who have no interest in becoming coupled.

Showing availability through marital status or presence or absence of other partners is a way of announcing goals in joining an online venue. Dating sites provide boxes where people can check off any or all options that people look for in signing up with a profile. They ask daters to select and mark their own marital status and the status of people they seek to encounter. Some sites explicitly limit their membership to those people are currently single who want committed relationships, while others permit different marital statuses and more casual goals. The mainstream sites often classify goals into categories like “long-term relationship” or “serious relationship”, “short-term relationship”, “friend”, “activity partner”, or “casual dating” or “play”. Newcomers can choose one or more of the goals. People who check off “discreet” or use the term in their profiles are understood to have other relationships, whether marriage or live-in partners.

The VC’s let people reveal in public or more privately their availability for relationships with those present in the discussion, the game or the chat room. Sometimes participants describe their spouses and children in their profiles, or they say who else lives with them, including pets. People may post photos or not, depending on community norms. Any information revealed about their age, marital status and place of residence is usually voluntary rather than fixed by categories provided at the site. VC’s differ in how much they require real names rather than just a user id, although many members know each other primarily by their nicknames. At some VC’s, nicknames or “nicks” relate to the subject matter of the group, such as fans of rock groups who name themselves after band members or particular songs. In others, like those on the dating sites, the nick either describes a personal interest or hobby, or, very commonly, is a form of their real names.

Types of places and frequency of personal relationships

In two seminal studies of relationships in cyberspace, Parks and his co-authors (Parks & Floyd, 1996; Parks & Roberts, 1998) determined that the majority of people in two types of online groups had formed at least one “personal relationship” The authors studied people in newsgroups, threaded discussion groups on topics of interest, and later, in MOO’s, which are text-based virtual realities, “object-oriented” MUD’s, or Multi-User Domains, most commonly used for role-playing games. Of people in newsgroups (Parks & Floyd, 1996), 60.7% started relationships, while 93.6 in MOO’s (Parks & Roberts, 1998) did so, most commonly building friendships. The researchers found that the majority of those forming relationships progressed to another communication channel outside of the group itself, including phone and snail mail. About a third in both types of online communities had gone on to meet face-to-face (f2f). People in MOO’s (1998) formed many more romantic partnerships than the members of newsgroups (1996), 26.3% to 7.9 %.

The size of the groups and the goal of the groups made a difference in numbers of people starting online relationships with each other. The immediacy of the communication, in real time in MOO’s, as opposed to asynchronous posts on a discussion board may contribute to the number of relationships developed, along with the group size and goal. Within the newsgroup, the level of experience or length of time in the group and frequency of posting affected the likelihood of forming a relationship (Parks and Floyd,1996).

In a study of MUDs, (Multi-User Domains), Utz (2000) found that more 76.6 % of her respondents, members of three online adventure games formed personal relationships. Her research highlighted the role of a player’s goal in the degree of involvement in bonding between members. The people most likely to connect with others outside the game play were first, those uninterested in either game playing per se or in role-playing, people there for the interaction online. The role-players were slightly more interested than the game players, whereas those sceptical that friendships could occur online did not form them as much as the other three groups. Those players also used much less “paralanguage” or emoticons and “emotes”, nonverbal expressions common in MUDs and MOOs. These include “smilies” such as and :-D as well as phrases indicating nonverbal reaction to what others say such as applause or blowing kisses. The average participant experience in the MUDs studied by Utz was 19 months, similar to Parks and Floyd’s typical newsgroup member, who was there for two years.

The process of initiating relationships in dating sites and VC’s

The process that occurs in identifying and contacting potential partners online differs for with those who meet in online dating sites (DS’s) as opposed to those who meet in online communities (Baker, 2005) or virtual communities (VC’s). In this chapter, the two terms online community and virtual community are used synonymously, to mean social groups of people interacting via the Internet. The term “virtual community” (Rheingold, 1993) became popularised early in the history of the world-wide-web, whereas “online community” arose later, to emphasize how these groups were taken more seriously, had more “real” impact than the original term perhaps implied. Couples encounter potential partners differently, whether looking specifically for others who meet a formal or informal set of criteria at dating sites, or running into them while participating in more ”naturalistic” (McKenna, 2007) settings, or at groups outside the dating sites.

Before the first meeting with the other person online at a dating site (DS), the online daters (1) see others in a setting delimited by their individual parameters set to include the kind of people they consider desirable. Then they can choose to click on any profiles that turn up within the search criteria. In this first online encounter of a potential partner, online daters see only the profile or online ad, and recently, on some sites, can access a voice-recorded message if someone has paid to put one up. The joiner of the virtual community (VC) sees all those who are online at the time he/she goes on. The VC person may talk/write in real time, synchronously, seeing what happens from the time of log-in. In a lag situation, the asynchronous, posters respond at their leisure to previously written comments, even though people may post within seconds of each other, mimicking real time interactions.

Selection of potential partners (2) can happen very fast in online dating sites. During each log-on, daters tend to select people quickly in one-shot explorations of profiles, whereas VC members get to know each other over time, and have access to previous posts going back weeks, months, and years, if the VC is old enough. In VC’s people see each other’s names in each posting and thus become familiar with each other in that sense (McKenna & Bargh, 2000). On the other hand, knowledge of hobbies and characteristics not specified during written participation in the community may or may not appear in profiles of VC members. Photos typically do not show up in VC profiles, unless the community norms mandate them, whereas many on the dating sites post pictures of themselves contained in their ads or they exchange them by email. Matching occurs (3) automatically in a dating site through the software, with profiles appearing that were set to match the criteria specified by the user. The online dater can change the criteria at any time, to increase or decrease the available pool of matches. In a VC, matching is completely under the control of the individual participant.

In the online dating site, (DS), people usually express interest (4) by sending an email or “wink” to the person selected. The site conceals the private email addresses to allow only communications through the site itself, until the participants decide to exchange personal email addresses. In some cases, the daters may use instant message to indicate desire to connect, if the site has that option. In a VC people use “backchanneling” or communication outside the public board to indicate interest in developing further conversation. This usually happens through email or a private message, (PM) or instant message (IM), at first. In a VC people can post publicly too, expressing tastes or views that concur with the other person’s before going to a private mode of communication. Ultimately, the mechanism of personal connection is similar, although the amount of knowledge may vary greatly at each type of site.

The online dater may have expounded at length about themselves, or not very much at all, dependent on personal inclination and the structure of the dating site and its profiles. In the VC, the participants may see each other write or play or chat for long periods of time and can often access archived writings. A woman talks about her searches on a discussion forum for information about Leon’s history there:

One of things that I did, Leon had been there for a year…I went back through

every thread, searched out every single word, wanted to know if he was flirting

with other women...I wouldn't had been interested in him if he had been…

His interest was in the things that I was interested in. The environment. I liked the

fact that he was an artist...His tone...His spirituality came through. When I started

to realize how spiritual he was, I went back into all the things he wrote in

Spirituality...I went back to every conference and read everything he wrote…for a

lot of reasons. He used the same tone with other women...I am so monogamous, I

had to make sure person I was with was monogamous (Margo, phone interview).

Another person talks about what she liked better about VC’s than meeting men elsewhere:

I could see good things in the way Ferris responded to others' postings online,

as well as with me. One thing that didn't work about past online relationships

was that I could not observe the men interacting with others with any depth.

It was always one-on-one contact. But the format of the Cafe allowed for

community, a wide range of conversational topics, a good deal of depth of

conversation, and a great opportunity to observe other people interacting in a

variety of styles (Miranda, interview, email).

VC’s often have archives going back to their beginnings, allowing participants to see prospective partners’ posts about a variety of subjects, and to see how they present themselves and respond to others. Of course, a dater may do a search to see if information on the other person pops up online, or may pay for services that identify

current addresses and presence or absence of criminal records.

Types of places: Technical features

Some sites require or encourage avatars, member-created visual self-representations that accompany an online name. Depending on the site, avatars may include cartoon figures or photos (see Suler, 1996). Avatars are usually found in games, large and small and also places like The SIMS and Second Life, virtual worlds, where people meet to interact in various types of conversations and activities, and to buy virtual property and build virtual dwellings. Some of these sites require payment either to join or to attain privileges at higher levels and thus, resemble the dating sites that usually ask members to pay if they want to contact others, beyond a brief trial period. Most discussion boards online are free or based upon voluntary contributions although the long-lived board The WELL (www.well.com) and the recent incarnation of Salon Table Talk (tabletalk.salon.com) charge members to join.

Technical features of sites influence outcomes of interaction, in that availability of photos, chat mechanisms, and more recently web cams and voice recordings may encourage authenticity. People intent on circumventing honesty, however can concoct completely false identities, a practice much less common than popular news accounts portray (see Lenhart et al., 2001). On a dating site with age categories, people sometimes adjusted their ages slightly downward, reasoning that they would not appeal to those younger potential partners if they didn’t (Ellison et al, 2006). They saw this as acceptable within the site parameters, and often revealed their deception to others in the first email or two. Places with interaction of avatars allow people to create likenesses of themselves or or to create characters very different from themselves, such as fantasy creatures or animals. Norms of each place and available options influence the forms of the avatars. The site may offer individuals a variety of clothing, hairstyles, headgear or other add-ons such as wings of different sizes and shapes. A participant in online games, Taylor has written about how designers control images projected by the range of choices they offer to members of virtual worlds (2003). People in games and virtual worlds share how much or little they match their avatars in conversation with other avatars, either on site or through the backchannels of private chat or email.

Places to meet online and offline: Geographical distance

Wherever people meet online, if they like each other, they may want to meet in person, or offline. Leaving out the “exclusively internet-based relationship” (Wright, 2004),

online daters or friends wishing to deepen their connections often desire to encounter the person “in the flesh”. Early computer aficionados contrasted the virtual world with physical space by calling the offline world “real life. People from online would arrange not for a meeting, but a “meat” in “meatspace”, still part of the hacker’s dictionary (online jargon file, Raymond, 2003) to distinguish the earthy physical space from the ethereal cyberspace.

The following sections describe how the type of meeting place online relates to the geographical locations of participants. Although most people available for new relationships may well desire potential partners who live within walking distance, where they set their outer limits of travel distance varies. Residents of remote or rural areas may realize that potential partners live a number of miles away, whereas people in New York City perceive that many others of all ages, and interests live within a small geographical area. More commonly before the internet, and also today, people ranked

cities according to the number of singles there. Online, the type of place makes a difference in who tends to show up, and from where. Members of dating sites and VC’s may delimit their geographical boundaries differently. Deciding where to meet in person involves the variables of picking the particular kind of meeting place for the offline setting, as well as choosing the geographical location for the first encounter.

Meeting place online and place of residence of partners

On the dating site the importance of place outweighs many other factors, perhaps following only appearance and age for people who will not travel to meet others. At the site, partners can pre-limit the distance they search within. Meeting in a VC suggests that members come from many physical locations, if the VC does not emerge from a locally-based offline group. A VC may have an international membership or one limited to a particular country, if the native language is required. The location of the originating group or the founder may influence the residency of a typical participant, at least at first. Theoretically, on the internet, any space is open to those with access to it.

When people encounter those who live out of their geographical area, they either reject them, as on a dating site when their settings say someone must live within so many miles of their home, or they go ahead, nonetheless, with pursuing a relationship. The geographical distance between potential partners is a factor among people who wish to pursue relationships wherever they happen to meet online. Overcoming distance at various stages of the relationships may involve sticking with online communication modes, and then moving to long distance phone calls. With available cell or mobile phone plans and online long distance services like Skype, the financial cost may have declined from the past. At some point, partners have to decide who is going to travel to the other when they meet offline. If the relationship continues, eventually the partners will choose where to live, in either of their current locations or somewhere else. Sometimes they strike a deal whereby one offers to move, if the other agrees to eventually move where they like.

As people hit if off in the naturalistic settings, they may tend toward openness in how far they will go geographically to meet their partners. They are united by common interests, and have likely already built a satisfactory bond before they decide to proceed further. Comfortable with chatting or posting with those they might never meet offline, they can take the time to discover if they would like to share more of their lives than they already do.

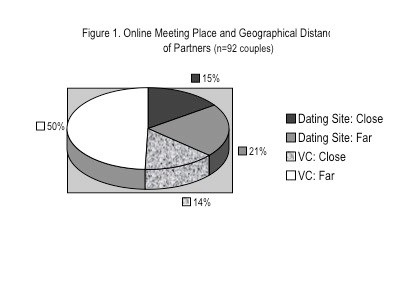

In the researcher’s study of 92 internet couples, 89 from Double Click (2005) and three more gathered later on, a third met on dating sites, with another third at real time chat groups or online games. The final third were from discussion boards, posting asynchronously. Combining the people at chats, games and discussion boards shows that nearly two-thirds of the couples met at VC’s (See Figure 1.) These people who met outside of dating sites tended to talk to those far way from them in geographical distance more than those from the matchmaking sites. The classification of “far” means that each member of the couple had to live outside the state of the other, for the U.S., and outside the province or country for Canada and Europe, or further away. Thirteen couples contained partners were from two different continents, mainly Europe and North America, with two people from Asia and two from Australia. “Close”, conversely, means individuals who lived no further than within the state, province or country of residence of their partners.

Observing online meeting place by geographical distance offline or comparative place of residence of the individuals within each couple, the pie chart in Figure 1 illustrates that half the sampled couples in the study met at VC’s and the individuals in them resided far from each other. The other half was split among the other three groups: dating site couples living further away, dating site couples who lived closer, and VC couples who resided relatively close by each other, rather than far.

These figures are not to suggest that most members of couples who meet online come from places distant to each other, but to identify where the people studied reside at first and later on in the development of their relationships. Each research project about online dating or relationship formation likely has a different mix of those geographical couplings, depending upon the dating sites or VC’s studied, as well as how the sample was gathered. Differences in findings may relate partly to variations in online and offline places of study participants. Online research that traces movement from online to offline locations should take into account the geography of both the online and offline meeting places.

Meeting offline: Choosing a place

People exploring relationships usually come to a juncture where they want to meet in person, to see if the connections they have explored will go further offline. They especially want to know if they “click” in real life the way they have online. Aside from deciding which mode they prefer for communication, the pair choose where to meet offline. They pick from a range of offline places, from coffee shops to restaurants and from hotels to their own homes, if they plan to stay overnight. Couples may decide before the actual meeting that they need a plan “B”. an exit route if they would rather not spend the original amount of time planned. Conversely, some couples may extend their visits, finding their partners particularly interesting (Baker, 2005). If staying overnight, they often have decided if they will consider sharing sleeping quarters or not.

Here is where geographical distance as well as length of time of communication can influence people’s choices. When people live in the same city, they can plan to meet briefly, to validate each other’s impressions. When far away, the travelling partner, or both people, if meeting at a neutral location, has committed more time and money to the meeting. Ironically, people who met at their own private residences had more chance of success or probability of staying together (at the last time of contact by the researcher) than did couples who met at hotels and other public places. These people generally communicated for longer periods of time, and may have felt quite comfortable with each other by the time they made the decision on where to meet offline.

Much more research is needed on how couples select their offline meeting place and how the place fits with the length of their communication and further development of their relationship or its decline. The quality of communication allows the couple to mutually fix the location of the beginning of their offline relationship, if the meeting carries the mutual attraction and friendship forward. The location can mark the relationship’s ending if either or both do not like what they see, hear, or feel from the other person.

The intersection of place and timing: Two dimensions of online relationships

While timing could be the subject of another article, here it is discussed as it relates to the places people meet online and offline. Place and timing interact in a number of different ways to develop or retard the online relationship. In this paper, “timing” means the sequence and length of events in the process of communication online and offline. The concept of timing encompasses decisions of when to move forward or not, and when to escalate the bonding through various means of communication. Timing also refers to method of communication and whether or not people interact in real-time or as if co-present in space, or not, engaging in a delayed response mode.

Bringing in time or timing into the process of online relationships sets up the notion of relationship stages. Depending on place, the relationship has a certain beginning as described above, either reading profiles and emailing or interacting in an online group. In either track, people may progress to another deeper stage of relating, if they decide they

are compatible. People coordinate the speed at which they progress, reaching a balance of mutual desire to continue, or conversely ending their interaction.

The topics here include mode of communication, whether in real time or not, and relation to place. Also discussed is the length of time before meeting and its dependence on place, and finally, an examination of the effects of place and time, moving toward an understanding of factors in the success of online relationships,

Synchronous vs. asynchronous communication and place online

Some online spaces are chat rooms, allowing participants to write in real time. Game players also relate in real time in places called “virtual worlds”. Virtual worlds are simulated environments where people interact using avatars. Someone new to the virtual world of Second Life comments on how the immediacy of synchronous communication affected her:

I have been very active in SL and have formed several relationships. As a

result, I experimented a bit with “textual intercourse” in SL and then in

chat—got seduced actually—and I was really surprised at now much impact

typing can have on you! But I am generally turned off by the more blatant

sexual overtones, and just like RL, I prefer intimacy to raw sex”

(Cassie, online posting, used by permission in email).

Some places contain only asynchronous options, such as posting in discussion boards, or sending email. Other spaces, although mainly asynchronous, have chat or IM options built in for people who wish to use them whenever they like. Within those places, whether an online dating site or a VC, if communication is usually asynchronous, a feature showing when someone is in the chat room helps avoid the situation of waiting silently for another chatter to show up.

One feature of online relationships is deciding on communication mode after the couple meets. If two people meet through chat, they may typically continue that or switch to the phone. Joe Walther’s early work (1992) has documented how even synchronous written communication proceeds more slowly, taking more time than verbal talk, causing some couples to proceed to the phone and use that as their main medium. If a couple meets by searching profiles and then emailing, or discussing issues at an online forum, they can decide to stay with email, which allows for thought and revision, unlike the real-time media. Of crucial importance is that the two must agree on the best communication mode to use to develop their relationship.

Time and place: Delay before meeting offline and type of online meeting site

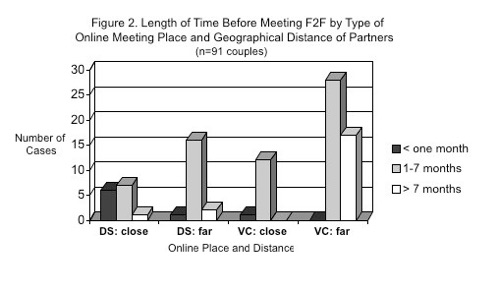

The data gathered from the 89 couples in Double Click (Baker, 2005) plus a few more couples joining the research later (n=91 pairs, not counting the one couple not meeting offline) includes geographical distance of the partners, type of site or place they met online, and amount of time lapsed between their online and offline meeting. Table 1 shows a relationship between the place they met and the timing of the lag between their

online and offline meeting.

(Insert Table 1 here)

Table 1. Time of Meeting Offline by Place of Meeting Online and Distance

(n=91 couples)

Dating site

VC

close far

close far | totals

Less than a month

6

1

1

(8)

One to three months

7

13

10

13

(43)

Four to seven months

3

2

15

(20)

Eight to 11 months

1

4

(5)

12 months or over

1

1

13

(15)

totals

(14)

(19)

(13)

(45)

(91)

Most of the members of couples who waited the longest times to meet, a year or more, were from geographically distant places. Noteworthy too, and perhaps less obvious is that most couples who met at VC’s rather than dating sites took a longer time to meet. Two couples from VC’s with geographically distant relationships even waited more than two years to meet. (Even with collapsed cells, some contain cells with n’s too small for statistical analysis.)

Collapsing the five categories into three lengths of time before meeting offline, less than a month, one to seven months, and more than seven months produces the bar graph, Figure 2. It shows people in dating sites (DS) typically meet in a short rather than a long period whether they live close or far, whereas people from VC’s usually engage in longer online correspondence or phone contact before meeting offline, especially when they live far away. People in DS have presumably committed to meeting potential partners by joining the site, although some members browse profiles without seeking to connect further. Converting the raw data from Table 1 and Figure 2 into percentages shows that 21% of those from dating sites met within a month or less, whereas only 2% of VC participants did. Conversely, 29% of people from VC’s took seven months or longer to meet offline, while only, 9% of people from DS’s waited that long, regardless of geographical distance. Although the sample was not random, an issue for researchers of online relationships is to specify both the distance between partners and the type of site of their study participants before drawing conclusions from their data about timing of offline meetings.

Almost all of the couples who waited a year or longer to meet offline met at virtual communities, not dating sites. They came to know each other in a more “naturalistic” way (see McKenna, 2007) rather than seeking out a dating partner or mate directly. Most of the people who met within a month’s time came from dating sites. These daters wanted to interact f2f with potential partners quite quickly, which was easier to accomplish when they lived closer. No one from a VC in the couples studied met in less than a month after meeting first online.

Place and Deception: The online presentation of self

While an in-depth treatment of the issue of online deception is beyond the scope of this paper, a few points about place or settings, goals and honesty can be made. (For comparisons of self-revelation and honesty online versus offline, see, for example, Cornwell & Lundgren, 2001; Hancock et al., 2004; Joinson, 2001; Tidwell & Walther, 2002). At dating sites (DS), no real names are used, unless a first name is combined with some numbers or another word. The process of revealing identity usually follows a path from on-site email to personal email to phone number before meeting in person. The two people control the flow of information. In VC’s, anonymity ranges from none at all, with people using true or real first and last names to total protection of identity, with people hidden by avatars and names chosen from site-provided lists as in Second Life. In chat rooms people regularly select nicknames related to the topic area and in some discussion boards, such as fan groups people choose names derived from the celebrities or shows of interest.

When people wish to know each other more than casually, the issue of honesty rises in importance. Upon entering any site, a person can decide which level of honesty appeals to him or her within the technical parameters and norms of the site, coupled with a personal preference within those constraints. On a discussion board, members become known to each other by their histories there and in interactions elsewhere. One interesting feature bringing the two settings closer is that some dating sites (see http://www.plentyhoffish.com) now have opportunities for daters to speak about each other after they communicate, either affirming or disconfirming what is presented by a dater.

Goffman (1956) described how people present themselves in social situations, how they “manage impressions” of others by highlighting positive features and de-emphasizing or hiding negative ones. Rather than divide online participants into honest and deceiving, researchers may want to look at the slight deceptions prevalent at dating sites as commonly accepted attempts to present an appealing persona. People who want to develop relationships know that any major deceptions will emerge over time. Based on cases of couples that were available for analysis during the years of the data collection, Baker (2005, 2002) found that people meeting online who lied about crucial facts such as marital status had less success in maintaining their relationships than those who were honest.

Place, timing and outcome: A concluding note on the success of online relationships

Building a framework from the data of couples that met online, this author (Baker, 2005) coined the acronym POST to discuss which couples seemed to have greater chances of success (Baker, 2005, 2002), or of creating marriages and other long-term intimate relationships. For the (P) factor, place of meeting affects which kinds of people are at a site, influencing degree of common interest, and affecting mutuality of goals. Examining the type of place where people meet online, and then also offline is crucial in understanding the dynamics of online relationships. People who meet in VC’s and in their homes offline seem to have a better chance of success, overall than others. Not discussed in this chapter, variations in handling the obstacles (O) a couple faces, and how each chooses to present himself or herself online, or self-presentation (S), as noted above, fill out the model. Here analysed mainly in conjunction with place, timing or (T) includes responding to the person’s initial contact to deciding when to move to another medium, how intimate to become online, and as outlined in this chapter, when to take the relationship offline.

Communication affects all four factors of the POST model, and of course, the four factors may affect the quantity and quality of communication as well. Communication skills and modes determine how the couple reacts after first encountering each other online in a particular type of place, and how the two people can overcome any obstacles such as distance, finances and other relationships to decide on a place to meet offline. Decisions about how to present themselves to the other involve choices about each dater’s honesty, with or without mild to extreme withholding of personal information or outright deception. Communication affects the timing or pacing of shared thoughts, feelings, and movement to the next level of commitment in continuing or stopping the relationship. The textual communication of the couple is the product of their online interaction. It constitutes the whole of the online relationship, unless audio or visual means of communication supplement the written word.

The details of types of online places examined here, along with the relations of aspects of time to place, can help future researchers specify patterns and problems in the development of online relationships. Whether at dating sites or virtual communities, the number of people forming intimate partnerships continues to grow worldwide (see Barak, 2007). Researchers can complement and inform each other’s work by stating not only “who” they are studying, but “where” people have found their partners online, and how that place makes a difference to the relationship process.

References

Baker, A. (2005). Double Click: Romance and Commitment Among Online Couples. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Baker, A. (2002). What makes an online relationship successful? Clues from couples who met in cyberspace. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 5(4), 363–375.

Baker, A. (1998). Cyberspace couples finding romance online then meeting for the first time in real life. CMC Magazine, July. http://www.december.com/cmc/mag/1998/jul/baker.html

Baker, A., & Whitty, M. (2007). Researching romance and sexuality online: Issues for new and current researchers. In Holland, S. (Ed.), Remote relationships in a small world. New York: Peter Lang.

Barak, A. (2007. Phantom emotions: Psychological determinants of emotional experiences on the internet, In Joinson, A., McKenna, K., Postmes, T., and Reips, U. (Ed.). Oxford handbook of internet psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bargh, J., McKenna, K. Y. & Fitzsimons (2002). Can you see the real me? Activation and expression of the “true self” on the internet. Journal of Social Issues, 58(1), 33-48.

Ben Ze’ev, A. (2004). Love online. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Berscheid, E. & Walster, E. (1978). Interpersonal attraction. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Byrne, D., London, O., & Reeves, K.. (1968).The effects of physical attractiveness, sex, and attitude similarity on interpersonal attraction. Journal of Personality, 36(2), 259-271.

Carter, D. (2005). Living in virtual communities: An ethnography of human relationships in cyberspace. Information, Communication & Society, 8(2), 148–167.

Cornwell, B., & Lundgren, D. (2001). Love on the Internet: Involvement and misrepresentation in romantic relationships in cyberspace vs. realspace. Computers in Human Behavior, 17 (2), 197-211.

Cooper, A. & Sportolari, L. (1997). Romance in cyberspace: Understanding online attraction. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 22(1), 7-14.

Cooper, A. (1999). Sexuality and the Internet: Surfing into the new millennium. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1, 181–187.

Cooper, A., McLoughlin, I., & Campbell, K. (2000). Sexuality in cyberspace: Update for the 21st century. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 4(3), 521-536.

Duck, S. & Craig, (1975). G. Effects of type of information upon interpersonal attraction. Social Behavior and Personality, 3(2), 157-64.

Ellison, N., Heino, R.,, & Gibbs, J. (2006). Managing impressions online: Self-presentation processes in the online dating environment. .Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(2). .http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol11/issue2/ellison.html.

Fiore, A. T., & Donath, J. (2004). Online Personals: An Overview. Paper presented at the meeting of ACM Computer-Human Interaction 2004, Vienna, Austria. Retrieved October, 1, 2004, from http://smg.media.mit.edu/papers/atf/chi2004_personals_short.pdf.

Framboni, R. (2004). Marriage market and homogamy in Italy: an event history approach. National Statistical Office. Retrieved Feb. 1, 07, from http://paa2004.princeton.edu/download.asp?submissionId=41515.

Gibbs, J., Ellison, N., & Heino, R. (2006). Self-presentation in online personals: The role of anticipated future interaction, self-disclosure, and perceived success in Internet dating. Communication Research, 33(2), p. 1 – 26.

Gibson, W. (1984). Neuromancer. New York: Ace Books.

Goffman, E. (1956) The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Doubleday.

Hancock J., Thom-Santelli, J., & Ritchie, T. (2004). Deception and design: the impact of communication technology on lying behavior. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 129-134.

Hatfield, E. & Sprecher, S. (1986). Mirror, mirror: The importance of looks in everyday life. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Joinson, A. (2002). Understanding the Psychology of Internet Behaviour: Virtual Worlds, Real Lives. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Joinson, A. (2001). Self-disclosure in computer-mediated communication: the role of

self-awareness and visual anonymity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31(2).

177-192.

Konner, J. (2006) (Executive producer and writer). The Mystery of Love. PBS.

http://www.themysteryoflove.org.

Lenhart, A., Rainie, L., & Lewis, O. (2001). Teenage life online: The rise of the instant-message generation and the Internet's impact on friendships and family relationships. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project.

McKenna, K. Y. (2007). A progressive affair: Online dating to real world mating. In Whitty, M., Baker,, A. & Inman , J. (Eds.), Online Matchmaking. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave MacMillan.

McKenna, K. Y. & Bargh, J. (2000). Plan 9 from cyberspace. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(1), 57-75.

McKenna, K. Y., Green, A., & Gleason, M. (2002). Relationship formation on the internet: What'’s the big attraction? Journal of Social Issues, 58(1), 9-31.

Merkle, E.. & Richardson, R.. (2000). Digital Dating and Virtual Relating:

Conceptualizing Computer Mediated Romantic Relationships. Family Relations. 49(2), 187-192.

Parks, M. & Floyd, K. (1996). Making friends in cyberspace. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication [On-line], 1(4). Available: WWW URL http://www.usc.edu/dept/annenberg/vol1/issue4/parks.html

Parks, M. & Roberts, L. (1998). ‘Making Moosic’: The development of personal

relationships on line and a comparison to their off-line counterparts. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 15(4), 517-537.

Pilkington, N. & Lydon, J. (1997). The relative effect of attitude similarity and attitude dissimilarity on interpersonal attraction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(2), 107-122.

Rabby, M. & Walther, J. (2002). Computer-Mediated communication in relationship

formation and maintenance. In D. Canary and M. Dainton (Eds.), Maintaining

Relationships Through Communication. Lawrence Erhlbaum Mahwah: NJ.

pp. 141-162.

Raymond, E. (2003) (Ed.) The on-line hacker jargon file, version 4.4.7. http://catb.org/jargon/html/M/meatspace.html.

Rheingold, H. (1993). The virtual community: Homesteading on the electronic frontier.

Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley.

Strate, L. (1996). Cybertime. In. L. Strate, R. Jacobson, & S. Gibson (Eds.), Social interaction in an electronic environment. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Suler, J. (1996). The Psychology of Cyberspace. http://www.rider.edu/~suler/psycyber/psycyber.html

Taylor, T. L. (2003). Intentional bodies: Virtual environments and the designers who shape them. International Journal of Engineering Education, 19(1), 25-34.

Tidwell, L. & Walther, J. (2002). Computer-mediated communication effects

on disclosure, impressions, and interpersonal evaluations: Getting to know one another a bit at a time. Human Communication Research, 28 (3), 317–348.

Utz, S. (2000). Social information processing in MUDs: The development of friendships in virtual worlds. Journal of Online Behavior, 1(1). http://www.behavior.net/JOB/v1n1/utz.html

Wallace, P. (1999). The psychology of the internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Walther, J. (1992). Interpersonal effects in computer-mediated interaction: A relational perspective. Communication Research, 19, (1), 52-90.

Wheeler, R. and B. Gunter. (1987). Change in spouse age difference at marriage: A challenge to traditional family and sex roles? The Sociological Quarterly,

28 (3), 411-421.

Whitty, M. & Carr, A. (2006). Cyberspace Romance: The psychology of online relationships. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave MacMillan.

Whitty, M. & Gavin, J. (2001). Age/Sex/Location: Uncovering the Social Cues in the Development of Online Relationships. CyberPsychology and Behavior. 4(5), 623-630.

Wright, K. (2004). On-line relational maintenance strategies and perceptions of partners within exclusively Internet-based and primarily Internet-based relationships. Communication Studies, 55(2), 418-432.

Wysocki, D. & Thalken, J. (2007). Whips and chains? Fact or fiction?: Content analysis of sadomasochism in internet personal advertisements. In Online Matchmaking (Eds.), Whitty, M., Baker, A., & Inman, J. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.