Viola palmata L. sensu lato [species complex]

Common names:

Three-lobed Violet

Synonyms:

See subordinate taxa.

Subordinate taxa belonging to this species:

Viola palmata L. var. palmata

Viola palmata L. var. triloba (Schwein.) Ging.

Viola "palmata avipes"

Viola "palmata glabrate"

Viola "palmata pseudo-stoneana"

Viola "palmata Red Hills"

Description:

Acaulescent rosulate perennials from thick rhizome, ≤ 36 cm tall; foliage and peduncles green to gray- or blue-green, lower surface of leaf blades sometimes paler than upper surface, often purple-tinged, petioles, peduncles and calyx often red-purple- to purple-spotted, foliage and peduncles moderately to densely hirtellous or hirsute (glabrous or sparsely hirsute in var. triloba and V. “palmata glabrate”); stipules free, glandular-fimbriate; heterophyllous, leaves ascending to spreading, earliest and latest leaf blades undivided (these occasionally lost or withered), largest in chasmogamous flower through mid-cleistogamous fruit shallowly to moderately lobed (in var. triloba, or divided nearly or fully to summit of petiole, deeply pedately divided (in var. palmata, V. “palmata avipes” and V. “palmata glabrate”) into 3, 5 or 7(9) lobes or biternately divided (in V. “palmata Red Hills” and V. “palmata pseudo-stoneana”) into 5 or 7(9) lobes, the largest ≤ 113 × 110 mm, outline ovate to broadly ovate, deltate or reniform, in summer broadening to deltate or reniform, base deeply cordate, margins irregularly or remotely serrate, ciliolate or ciliate, apex acute to broadly obtuse; chasmogamous peduncle held among the leaves; chasmogamous flower ≤ 28 mm; calyx glabrous, ciliate (auricles ciliate, sepals eciliate in var. triloba and V. “palmata glabrate”); lowest sepals oblong-lanceolate to ovate and obtuse to rounded (in var. palmata, var. triloba, V. “palmata avipes” and V. “palmata pseudo-stoneana”) or linear-lanceolate to lance-triangular and acuminate (in V. “palmata glabrate” and V. “palmata Red Hills”); auricles short and entire, not elongating in fruit; corolla blue to purple, throat white; spur short-globose; lateral petals densely bearded with narrowly linear or slightly clavate hairs, spurred petal glabrous; chasmogamous capsule green; cleistogamous flowers produced after chasmogamous, peduncles initially prostrate but arching upward just before capsule dehiscence, shorter than petioles, capsule 7–14 mm, green drying tan with purple spots or blotches, glabrous; seeds (1.7)2.0–2.5 × 1.2–1.5 mm, light brown to brown with small darker brown streaks or blotches; 2n=54.

Similar species:

Viola stoneana

Ecology:

Dry sandy, sandy loam or clayey soils in dry to dry-mesic woods, often on slopes or bluffs, and on margins of wetter forests, swamps or floodplains.

Distribution:

Widespread in eastern North America, ME to ON and WI, south to FL and TX.

Rarity:

None.

Phenology:

Chasmogamous flower Mar–Jun, chasmogamous fruit Apr–Jul, cleistogamous fruit May–Oct.

Affinities:

This species belongs to the Acaulescent Blue Violet lineage, sect. Nosphinium W.Becker, subsect. Boreali-Americanae (W.Becker) Gil-ad, in the Palmata species group.

Hybrids:

See subordinate taxa.

Comments:

Elliott (1817) and other botanists within half a century of Linnaeus (1753) routinely described a heterophyllous violet when referencing the name V. palmata L. In oppposition, Brainerd (1910c) argued vehemently that the name should be attributed to the homophyllous cut-leaved violet predominately distributed in the Appalachian Mountains and associated uplands. He proposed taking up the name V. trilobaSchwein. for the widely distributed heterophyllous violet. For the southern heterophyllous violet with mid-season leaf blades deeply 3- to 5-lobed, he created the new combination V. triloba var. dilatata (Elliott) Brainerd. For the northern heterophyllous violet with shallowly to moderately lobed leaf blades, he applied the name V. triloba var. triloba. This taxonomic interpretation was followed by Brainerd (1921b), Brainerd Baird (1942), Fernald (1950), Henry (1953a), Alexander (1963), Russell (1965), Scoggan (1978), Strausbaugh and Core (1978), and Swink and Wilhelm (1979). McKinney (1992) examined the protologue and original material of Linnaeus's V. palmata and reinterpreted the name to refer to the heterophyllous violet known since Brainerd's time as V. triloba (including its var. dilatata), and he argued that the earliest available name for the Appalachian region's homophyllous cut-leaved violet was V. subsinuata (Greene) Greene. Gil-ad (1995, 1997) rejected McKinney's argument in favor of Brainerd's interpretation, retaining V. triloba Schwein. as the correct name for the heterophyllous violet and suggested that macromorphological features of Linnaeus's original material of V. palmata suggested hybridization between a homophyllous cut-leaved violet and a heterophyllous violet such as V. triloba. Gil-ad examined macromorphological features and micromorphology of lateral petal trichomes and seed coats of several specimens identified as V. triloba var. triloba and a few specimens from the Lower Midwest portion of the range of var. dilatata. He reported considerable variation in seed macromorphology and micromorphological features within and among the populations and specimens of var. triloba, as well as micromorphological features on seed coats similar to those found in V. affinis and V. sororia, suggesting introgression. Gil-ad's field observations of var. dilatata at three oak woodlands on limestone in Missouri supported Russell's statement that var. triloba and var. dilatata do not occur together. Gil-ad noted a number of macromorphological differences between the two varieties he studied, including density of foliage indument, features of the leaf blade, corolla color, density of calyx ciliation, shape of lateral petal trichomes, capsule shape, and seed dimensions. He was only able to examine partially mature seeds for micromorphological features but noted features similar to those on seeds of var. triloba as well as features similar to those of V. affinis, V. missouriensis, and V. nephrophylla. His data could not rule out the possibility of a hybrid origin for var. dilatata. Gil-ad accepted V. triloba sensu stricto as a distinct taxon but rejected var. dilatata as a probable hybrid derivative, mainly due to lack of unique seed micromorphological features. Ballard (2000, 2013), McKinney and Russell (2002), Haines et al. (2011), Weakley et al. (2012), and Little and McKinney (2015) adopted McKinney's interpretation of the names V. palmata L. and V. subsinuata, in most instances applying the former name to a broadly delimited assemblage of several species accepted here as distinct. Ballard (1995) and Voss and Reznicek (2012) merged the homophyllous cut-leaved violets (excluding V. pedatifida) and heterophyllous violets of Michigan into V. ×palmata and V. palmata, respectively, whereas Gleason and Cronquist (1991) conducted wholesale lumping of many formerly recognized heterophyllous and homophyllous cut-leaved taxa into a highly heterogenous V. palmata. I have made independent examinations of Linnaeus's protologue and original material and have arrived at the same conclusion as McKinney, that the name V. palmata L. unambiguously refers to the widely distributed heterophyllous violet previously attributed to V. triloba. Linnaeus's own description of Viola palmata, "Viola acaulis, foliis palmatis quinquelobis dentatis indivisisque", indicates that some leaves are palmately 5-lobed and others are undivided. Linnaeus next presents Gronovius's "Flora Virginica" description, followed by Plukenet's "Mantissa" description, and finally Plukenet's "Amaltheum" description. Gronovius's publication also cites Plukenet's "Mantissa" description and Plukenet's "Amaltheum" description but ends with the statement "Viola Martia coerulea inodora, radice tuberosa: foliis variis, aliis integris, aliis incisis. Clayt. n. 793". Once again, Gronovius specifically references a specimen that bears some undivided leaf blades and some divided leaf blades. In addition, the illustration in Plukenet's "Amaltheum" clearly depicts a heterophyllous violet, and the herbarium specimen on which it is based (LINN, image!) is a heterophyllous violet. As further evidence, the lectotype sheet (no. 486, Herb. Jacquin, LINN-HL1052-1, image!) and a syntype sheet (J. Clayton 468 & 793, ex Herb. Gronovius, BM000042617, image!) both display the deeply pedately divided leaf blade with 5 slender lobes characteristic of many southeastern plants which Brainerd and others have identified as V. triloba var. dilatata. One of Brainerd's lines of evidence arguing for a homophyllous violet as Linnaeus's V. palmata was the reference to Florida by Plukenet's "Amaltheum" description, and Brainerd asserted that the only pubescent cut-leaved violet he knew in Florida was V. palmata [the homophyllous taxon, in this treatment referred to as V. subsinuata sensu lato]. He was referring particularly to living plants and specimens sent to him by Agnes Chase from a single unspecified locality in Lake County, Florida. He maintained the living plants and made at least two more sheets. The specimens are anomalous, with two of three specimens producing deeply pedately divided (one specimen has a leaf scarcely pedately lobed) but with the lobing pattern on some leaf blades distinctly pedate and the venation on most leaf blades clearly pedate, suggesting a hybrid involving V. palmata var. palmata or V. septemloba with another species (or each other). Plants of a number of heterophyllous violet taxa lacking an undivided leaf are not rare. Contrary to Brainerd's statement that there are no pubescent heterophyllous violets in Florida, Russell (1965) maps his V. triloba var. dilatata throughout much of Florida and adjacent areas, and I have examined a substantial number of such herbarium specimens and a few living populations from northern Florida and adjacent southeastern states. The cumulative evidence is overwhelmingly in favor of the name V. palmata L. representing a heterophyllous violet, specifically that which has been regarded since Brainerd's time as V. triloba Schwein. To further confound matters, Linnaeus's original material consists of plants matching one of the deeply divided-leaved variations long referred to as V. triloba var. dilatata (Elliott) Brainerd and not of the northern shallowly lobed taxon called var. triloba. Gil-ad (1995, 1997) argued that the absence of leaves with undivided blades and the dissection pattern of the blades on Linnaeus's original material suggested a hybrid involving V. palmata (sensu Brainerd) and a heterophyllous taxon. However, both specimens are representative of one of the many leaf blade variations found in southeastern Piedmont and Coastal Plain populations treated by various taxonomists as V. triloba var. dilatata. Linnaeus's V. palmata therefore represents the more deeply divided-leaved southern taxon, which is correctly named V. palmata var. palmata. This renders V. palmata var. dilatata Elliott a synonym. The shallowly lobed northern taxon, retained here as a variety until further studies clarify its evolutionary and taxonomic status, requires a different name, and the earliest available name unambiguously applied to it is Viola palmata L. var. triloba (Schwein.) Ging. Gil-ad's findings regarding variability within disparate specimens of three-lobed var. triloba indicate that not all plants with similar leaf blade morphology are genetically pure (Brainerd reported repeatedly that hybrids with V. sororia produced progeny that resembled either parent but were substantially subfertile) or that not all plants with similar leaf blade morphologies are the same taxon. It is possible that Gil-ad's sampling included both typical var. triloba as well as hybrids involving other species, or that his results highlight additional taxa lurking in var. triloba. Nevertheless, the several macromorphological and micromorphological distinctions he enumerated between var. triloba and var. dilatata supports their continued recognition as distinct taxa. The question of hybrid origin for either variety–or any taxon accepted in this treatment–is a non-issue under the Unified Species Concept as employed here. As presently delineated, V. palmata sensu lato is an assemblage of taxa that probably represent several evolutionary species. Populations from the Lower Midwest were segregated by Greene as V. falcata early on but have since been included in eastern Piedmont and Coastal Plain V. palmata var. palmata, as reinterpreted here. The two sets of populations appear to diverge somewhat in features of blade dissection and seed traits, and they may occupy somewhat different microhabitats, but the extensive degree of leaf blade variation observed within populations in the two regions makes assessment difficult. The whole V. palmata species complex requires intensive investigation. Vitek et al. (2012) and Cheon et al. (2019) reported Viola palmata naturalized in Austria and Korea, respectively. Although no images of the plants were included in the first communication, the second report had photographs of the violet, and it is definitely not V. palmata. Elliott (1817), in describing V. palmata L. followed by four new varieties, stated that the three upper petals were bearded and the two lower were naked. Assuming he was cognizant of the resupinate nature of violet flowers, this would imply that the spurred as well as lateral petals were bearded. Henry (1953a) claimed that the spurred petal was bearded, but many other authors and I have confirmed the spurred petal to be glabrous in typical specimens.

Literature Cited:

Alexander, E. J. 1963. Violaceae. In Gleason, H. A., The new Britton and Brown illustrated flora of the northeastern United States and adjacent Canada. Hafner Publishing Co., Inc., New York, NY. 552-567.

Ballard Jr., H. E. 1995 ["1994"]. Violets of Michigan. Michigan Botanist 33: 131-199.

Ballard Jr., H. E. 2000. Violaceae. In Rhoads, A. (ed.). Flora of Pennsylvania. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA. 700-710.

Ballard Jr., H. E. 2013. Violaceae. In Yatskievych, G., Flora of Missouri. Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis, MO. 1218-1243.

Brainerd, E. 1910c. Viola palmata and its allies. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 37: 581-590, plate 36.

Brainerd, E. 1921b. Violets of North America. Vermont Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 224: 1-172.

Brainerd, E. 1924. The natural violet hybrids of North America. Vermont Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 239.

Brainerd Baird, V. 1942. Wild violets of North America. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Fernald, M. L. 1950. Violaceae. In Gray’s Manual of Botany, 8th ed. American Book Company, New York, NY. 1022-1042.

Elliott, S. 1817. A sketch of botany of South Carolina and Georgia. J. R. Schenck, Charleston, SC.

Gil-ad, N. L. 1995. Systematics and evolution of Viola L. subsection Boreali-Americanae (W. Becker) Brizicky. Ph.D. dissertation. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Gil-ad, N. L. 1997. Systematics of Viola subsection Boreali-Americanae. Boissiera 53: 1-130.

Gil-ad, N. L. 1998. The micromorphologies of seed coats and petal trichomes of the taxa of Viola subsect. Boreali-Americanae (Violaceae) and their utility in discerning orthospecies from hybrids. Brittonia 50: 91-121.

Gleason, H. A., and A. Cronquist. 1991. Violaceae. In Manual of vascular plants of northeastern United States and adjacent Canada, 2nd ed. New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 157-163.

Haines, A., E. Farnsworth, and G. Morrison. 2011. Violaceae. In Flora Novae Angliae. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. 873-886.

Henry, L. K. 1953a. The Violaceae in western Pennsylvania. Castanea 18(2): 37-59.

Linnaeus, C. 1753. Species Plantarum. Impensis Laurentii Salvii, Stockholm, Sweden.

Little, R. J., and L. E. McKinney. 2015. Violaceae. In Flora of North America: Cucurbitaceae to Droseraceae, 106. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

McKinney, L. E. 1992. A taxonomic revision of the acaulescent blue violets (Viola) of North America. Sida, Botanical Miscellany 7: 1-60.

McKinney, L. E., and N. H. Russell. 2002. Violaceae of the southeastern United States. Castanea 67: 369-379.

Russell, N. H. 1965. Violets (Viola) of the central and eastern United States: An introductory survey. Sida 2: 1-113.

Scoggan, H. J. 1978. Violaceae. In Flora of Canada, Part 3–Dicotyledoneae (Saururaceae to Violaceae). National Museums of Canada. Ottawa, Canada. 1103-1115.

Strausbaugh, P. D., and E. L. Core. 1978. Violaceae. In Flora of West Virginia, 2nd ed. Seneca Books, Inc., Morgantown, WV. 644-658.

Swink, F., and G. Wilhelm. 1979. Violaceae. In Plants of the Chicago region, 2nd ed. revised and expanded. Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL. 384, 801-810.

Voss, E. G., and A. A. Reznicek. 2012. Violaceae. In Field manual of Michigan flora. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 913-922.

Weakley, A. S., J. C. Ludwig, and J. F. Townsend. 2012. Violaceae. In Flora of Virginia. BRIT Press, Fort Worth, TX. 963-975.

Chasmogamous flowering habit of V. palmata var. palmata (plant from Boone Co., MO) by Kim Blaxland, "Botanikim" website (permission granted by Chris Blaxland)

Chasmogamous flowering habit of V. palmata var. triloba by Andrew Gibson, "Buckeye Botanist" website

Chasmogamous flowering habit of V. "palmata avipes" by Harvey Ballard

Chasmogamous flowering habit of V. "palmata Red Hills" from herbarium specimen: AL, Tallapoosa Co., (n. of Pollard) river hills, 26 Apr 1901, F. S. Earle s.n. (NY)

Chasmogamous flower front view of V. palmata var. triloba by Andrew Gibson, "Buckeye Botanist" website

Seeds of V. palmata var. triloba from herbarium specimen: Transplanted from OH, Athens Co., Sells Park, H. Ballard 15-055Z (BHO)

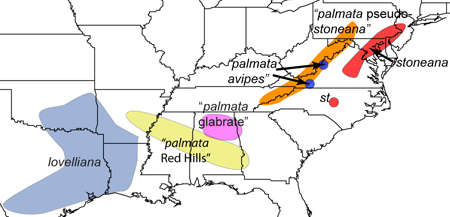

Map of widespread varieties of V. palmata by Harvey Ballard, adapted from Russell (1965)

Map of regionally endemic taxa in the Palmata species group by Harvey Ballard