Ecology of Vegetation and Plant SuccessionPrincipal Adaptive Strategies of VegetationPlants evolve a variety of adaptations to the light and moisture availability within a particular environment in order to flourish. Plants adaptations include those of leaf form and canopy structure (the roof of foliage formed by the crowns of trees). For instance, a hard, needle leaf structure is an adaptation to extreme temperatures and low moisture status in winter. The leaves of some rain forest trees have a special joint at the bottom of their stalk that enables them to twist and turn to follow the light as the sun passes from east to west over head. Deciduous trees drop their leaves to cut transpiration loss during dry periods and when temperatures are very cold. Conifer needles are an important adaptation to the extreme conditions present in the climate of the boreal forest. Pine needles contain very little sap, so freezing is not much of a problem. Conifer needles have a unique structure which limits the loss of water, a precious commodity in this environment. Pine needles have fewer stomata than broadleaf tree leaves. The stomata are recessed into pits on the needle and aligned in a groove on its underside. The groove in the needle creates a small layer of still air which slows the loss of water vapor by diffusion. Water loss is further reduced by the thick waxy coating common to pine needles. Water is "shut off" from the tree when the ground completely freezes. Under these circumstances the stomata close-up to prevent loss of water from the tree.

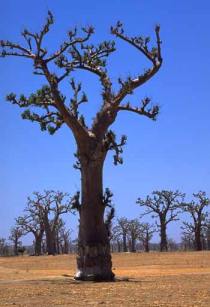

Fleshy "leaves", like those of desert succulents or thick skin like that of the giant Saguaro cactus helps retain moisture. The Baobab tree, found in the wet/dry tropical (savanna) climate stores water in its trunk to combat the long drought period experienced in that climate.

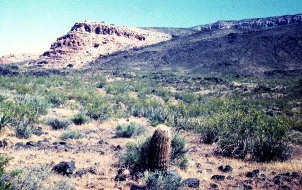

Plants have adapted particular root structures to live in arid regions. Deep tap roots draw moisture hidden deep below the surface while extensive near - surface root systems catch moisture as it infiltrates into soil. The Havard Oak (Figure 12.*) is a shrub found in the semi-arid southwestern United States. It is well adapted to the dry conditions having an extensive root system and tap roots that extend 15 to 20 feet deep. Tap roots "equal to a man's thigh" are not uncommon. Above ground, thick waxy leaves reduce water loss through transpiration.Some desert grasses have rolled surfaces to reduce water loss from the inner surface and hairs which reduce air movement. Figure 12.8 Havard Oak (Q. havardii) Photograph courtesy Michael Ritter Canopy structures reflect the environmental conditions

vegetation

grows in. The conical canopies of conifers help shed snow and catch low angle sun rays during

the long winters where they grow. The rain forest displays a

multi-layered canopy

|