|

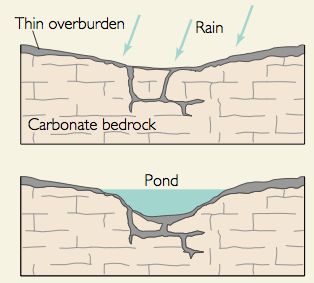

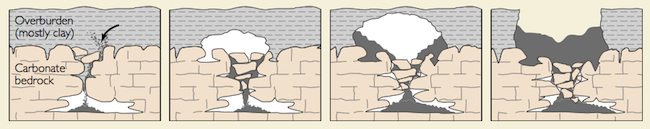

Weathering, Erosion, and Mass Movement Karst LandscapesThe chemical weathering of carbonate-rich rocks creates a unique landscape abounding in caves, disappearing streams, and springs. Karst, a Yugoslavian term that comes from a narrow strip of limestone plateau noted for the assemblage of solution landforms. Karst develops in regions underlain by limestone and to a lesser extent dolomite. Chemical solution of the limestone, especially when fractured, wears away the bedrock leaving fissures and possibly undermining the surface. Some of the most spectacular cave complexes are found in such areas. Significant karst regions are found in Jamaica, the northern Yucatan, New South Wales, northern Puerto Rico, the Great Valley Region of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and Tennessee, central Kentucky and central Florida in the United States

Generally four conditions are important for karst development. First, there must be limestone at or near the surface. Though karst is found in areas underlain by dolomite, it usually far less soluble than limestone. Second, the limestone must be dense, highly jointed, and thinly bedded. If the rock is too porous, water will be rapidly absorbed throughout the entire mass and not be concentrated along restricted flow lines. Third, the existence of entrenched valleys below uplands underlain by soluble and well jointed rocks ensures downward movement of groundwater, favorable for the development of karst. Finally, at least moderate precipitation must fall in the region. Few arid or semi-arid regions exhibit karst features, though some relic features may exist from a previous moist period in the past. Karst Landforms

|

Figure 17.5 Stalactites

hang from the ceiling and stalagmites grow from the floor of Carlsbad Caverns,

NM (Photo Credit: National Park Service)

Figure 17.5 Stalactites

hang from the ceiling and stalagmites grow from the floor of Carlsbad Caverns,

NM (Photo Credit: National Park Service)