|

|

|

Home Dr. Hembree Research Continental Ichnology Laboratory Students Publications Courses News and Opportunities Links

|

|

Welcome to the

Continental Ichnology Research Laboratory. The purpose of the CIRL is to

investigate the behaviors and biogenic structures (burrows, nests, tracks,

trails) produced by modern continental organisms in order to better interpret

trace fossils preserved in continental deposits throughout geologic time. |

|

Goals of the CIRL |

|

|

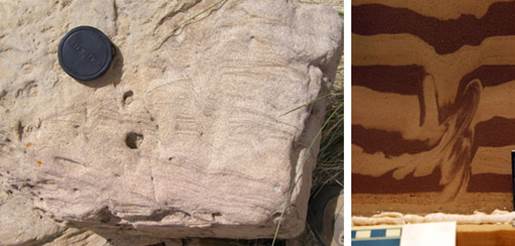

Research in the CIRL focuses on the burrowing behavior and

biogenic structures of extant terrestrial animals for application to the

study of ichnofossils. Ichnofossils provide

a critically important in situ record

of paleoenvironmental and paleoecological change that has become an essential

aspect of sedimentology, stratigraphy, and paleontology. By studying the behavior

of continental tracemakers, the morphology of their burrows, nests, tracks,

and other traces may be correlated to continental environmental factors such

as temperature and precipitation, depositional environments, and such

substrate characteristics as soil consistency, moisture level, and organic

content. In addition, if trace morphology can be linked to specific taxa or

body morphologies, then these traces may be used in lieu of body fossils to

determine the geographic and temporal range of different groups of organisms. |

|

|

Current Laboratory

Research Animals |

|

|

Sonoran Desert Millipede (Orthoporus ornatus) Small (10-15 cm long) millipedes that spend the majority of their

lives in the subsurface. They construct long-term dwelling structures in a

wide variety of soils and are capable of excavating very dense sediment. These millipedes inhabit semi-arid regions

but still require high moisture.

Construction of permanent burrows allows these millipedes to construct

microhabitats with high humidity. (Results published in PALAIOS, v.

24, p. 425-439) |

|

|

Giant African Millipede (Archispirostreptus gigas) One of the largest extant millipedes in the world (18-25 cm

long). Giant African millipedes produce sinuous burrows related to foraging behaviors.

If humidity drops too low, however, these millipedes will construct U-shaped

and W-shaped, temporary dwelling structures. Giant African millipedes will

only burrow into loose sediment and are unable to penetrate compacted or

clay-rich soils. (Results published in PALAIOS, v.

24, p. 425-439) |

|

|

North American Millipede (Narceus americanus) Medium-sized millipedes (6-10 cm long) that inhabit the eastern United States and portions of southeast Canada. They typically Occur on temperate to tropical forest floors at a variety of

elevation. These millipedes have high tolerance for dry and cold conditions,

burrowing into the soil to avoid desiccation or freezing. Narceus americanus burrows into a variety of sediments producing vertical, subvertical, helical, and O-shaped burrows. (Results published in Palaeontologia Electronica v. 17) |

|

|

Florida Scrub Millipede (Floridobolus penneri) Medium-sized millipedes (6-10 cm long) from Florida that move from

the subsurface to the soil surface during the night to feed. This continuous

movement acts to churns the soil, disrupting primary sedimentary structures

and leaving behind multiple irregular, open burrow segments and chambers

resulting in increased porosity and permeability. The bioturbation of these

millipedes overturns the soil moving organic material from the soil surface

to the subsurface. They produce vertical, subvertical, helical, J-, and

O-shaped burrows. (Results published in Palaeontologia Electronica v. 17) |

|

|

Emperor Scorpion (Pandinus imperator) One of the largest scorpion species, P. imperator reaches 15-20 cm in length as adults. They inhabit

the floor of tropical rain forests in West Africa and exhibit communal

behavior, living in groups of several individuals within large burrows.

Emperor scorpions will construct burrows within a few days if no other

shelter is available. These initial burrows are shallow, simple ramps, but

are extended into helical or branched complexes over time. Burrows produced

by two or more individuals have tunnels that are typically much larger in

diameter than the scorpions themselves. (Results published in Topics

in Geobiology: Experimental Approaches to

Understanding Fossil Organisms [PDF]) |

|

|

Malaysian Forest Scorpion (Heterometrus spinifer) A large scorpion (10-15 cm) that inhabits tropical forests of

Malaysia and Thailand. These scorpions exhibit some communal behavior but

tend to be more territorial and aggressive than P. imperator. H. spinifer

is a nocturnal predator that generally constructs simple, steeply dipping

ramp-style burrows with varying depth. Two or three individuals may occupy a

burrow for short intervals of time. Female scorpions construct large and

complex burrow networks, modified over time with their young. |

|

|

Arizona Hairy Desert Scorpion (Hadrurus arizonensis) One of the largest scorpion species in North America, H. arizonensis reaches 14-15 cm in

length. The species is found in the North American southwest (Sonoran and

Mojave deserts) and is adapted to hot and dry conditions. Hairy desert scorpions are solitary

nocturnal predators. They can construct elaborate spiral and U-shaped

dwelling burrows in consolidated sandy soil (some >2 m deep) that are used

as temporary to permanent dwellings. (Results published in Palaeontologia Electronica v. 15) |

|

|

Dune Scorpion (Smeringurus mesaensis) A small- to medium-sized (5-10 cm) scorpion that inhabits desert

environments with loose, shifting sand in Arizona and California. These

scorpions are well-adapted to dry climates and obtain all of their water from

their prey. S. mesaensis

is a solitary nocturnal predator that constructs simple, shallow burrows in

loose sand or sandy soil. |

|

|

Northwestern Forest Scorpion (Uroctonus mordax) A small- to medium sized (5-10 cm) scorpion that inhabits the

California coast and montane forests of the Cascades and Sierras at

elevations up to 1900 m. While they are most commonly found beneath rocks or

logs, these scorpions will also produce simple, steeply dipping ramp-style

burrows in sandy soils. |

|

|

Giant Vinegaroon (Mastigoproctus giganteus) These arthropods, also referred to as whip scorpions, are 2-9 cm

in length. They inhabit the southern and southwestern United States. They are nocturnal predators with poor vision

but the first two walking legs are modified as sensory appendages.

Vinegaroons use their pedipalps to excavate loose to compacted soils and

construct a diverse array of burrows from horizontal shafts, U-shaped

burrows, helical burrows, and interconnected burrow networks. (Results published in PALAIOS, v.

28, p. 141-162) |

|

|

Red Trapdoor Spider (Myrmekiaphila sp.) This genus of trapdoor spiders inhabits the southeastern United States.

They are 3-8 mm in length and yellowish-red to dark-reddish brown in color.

These spiders construct silk-lined burrows covered by a silken trap door. The

burrows consist of networks of interconnected vertical shafts and horizontal

tunnels. In shallow soils the majority of the burrow may be composed of

horizontal tunnels with several chambers and trap doors at the surface. |

|

|

African Trapdoor Spider (Gorgyrella sp.) Large (3-5 cm) trapdoor spiders that inhabit southern Africa. Gorgyrella constructs simple,

silk-lined, vertical to subvertical shafts often ending in an enlarged

chamber with a single, large silken trapdoor at the surface. Gorgyrella are ambush predators,

rarely leaving their burrows. (Results published in Palaeontologia Electronica v. 18) |

|

|

Western Desert Tarantula (Aphonopelma chalcodes) Large (7-25 cm) ground spiders that inhabit deserts of Arizona

and northern Mexico. These tarantulas construct burrows in sandy soil that

they rarely travel far from except to mate. The burrows are sealed during the

winter and the spider hibernates. Burrows constructed in the laboratory

include large, but simple, subhorizontal tunnels. (Results published in Palaeontologia Electronica v. 20) |

|

|

King Baboon Tarantula (Pelinobius muticus) Large (5-20 cm) ground spiders that inhabit scrublands and

grasslands of East Africa (Kenya, Tanzania). These tarantulas excavate

burrows using their well-developed back legs. Silk is placed at the burrow

entrance to detect vibrations. In the laboratory these spiders have

constructed vertical to subvertical shafts with high chimneys of excavated

sediment built around the burrow entrance leading to subvertical to

horizontal tunnels. (Results published in Palaeontologia Electronica v. 20) |

|

|

Tawny Red Baboon Tarantula (Hysterocrates gigas) Large (10-30 cm), aggressive ground spiders that inhabit tropical

to subtropical forests of Cameroon and Nigeria. They are the largest of the

Old World tarantulas. These tarantulas are reported to construct intricate

burrows within forest soils. In the laboratory these tarantulas have

constructed large diameter, deep burrows composed of vertical to subvertical

shafts leading to branching horizontal tunnels. The burrow networks have

multiple entrances and the tunnels are lightly lined with silk. (Results published in Palaeontologia Electronica v. 20) |

|

|

Wolf Spider (Hogna lenta) Small (1-3 cm) ground spiders that inhabit much of the eastern

United States from Ohio to Florida. Wolf spiders are active and aggressive

hunters that spend most of their time on the surface. They do produce simple,

vertical burrows, however, and females construct deeper burrows once they

have produced an egg case. (Results published in Palaeontologia Electronica v. 18) |

|

|

Florida Giant Centipede (Scolopendra viridis ) Originating from the West Indies, these centipedes are now common

in Florida. They are very aggressive predators but also spend a significant

amount of time in the subsurface. Scolopendra viridis produces dense networks of vertical and

horizontal cross-cutting burrows. They burrow by wedging their bodies through

the sediment. Sediment is displaced

horizontally and compacted but very little is transported to the surface. |

|

|

Desert Centipede (Scolopendra polymorpha) These burrowing centipedes inhabit

dry, sandy soils of deserts, grasslands, and forests of the southwestern

United States and northern Mexico in regions with a hot semi-arid climate.

They reach lengths of approximately 18 cm and are nocturnal predators that

feed on soil arthropods and small vertebrates. S. polymorpha burrows through a

combination of intrusion, compression, and excavation techniques to produce

J-, U-, and Y-shaped burrows as well as complexes of linked burrows. (Results published in PALAIOS

v. 34, p. 468-489.) |

|

|

Eastern Bark Centipede (Hemiscolopendra marginata) These burrowing centipedes inhabit

moist, organic-rich soils of the southeastern United States in regions with a

generally humid subtropical climate. They reach lengths of approximately 8 cm

and are nocturnal predators that feed on smaller soil arthropods as well as

earthworms, nematodes, and gastropods. H.

marginata burrows by intrusion and limited

excavation to produce J-, U-, and Y-shaped burrows as well as complexes of

linked burrows.. (Results published in PALAIOS

v. 34, p. 468-489.) |

|

|

Darkling Beetle (Tenebrio molitor) These beetles have burrowing larvae that inhabit a variety of substrates

in woodlands. Currently they have a world-wide distribution due to their use

as a food source, but were originally present in Eurasia. Darkling beetles

are generalist omnivores that feed on decaying plant material, fresh plant

material, decaying insects, and fungi. The larvae burrow by intrusion,

compaction, and excavation to produce shallow, open, straight to sinuous

shafts and tunnels with thin, discontinuous linings as well as unlined, ovoid

chambers for pupation. Adults produced vertical escape burrows originating

from the pupation chamber. (Results published in Ichnos v. 28) |

|

|

Darkling Beetle (Zophobas morio) These beetles have burrowing larvae that inhabit a variety of

substrates in woodlands. Currently they have a world-wide distribution due to

their use as a food source, but were originally present in South America.

Darkling beetles are generalist omnivores that feed on decaying plant

material, fresh plant material, decaying insects, and fungi. The larvae

burrow by intrusion, compaction, and excavation to produce shallow to deep,

open, straight to sinuous shafts and tunnels with thin, discontinuous linings

as well as unlined, ovoid chambers for pupation. Adults produced vertical

escape burrows originating from the pupation chamber. (Results published in Ichnos v. 28) |

|

|

Tiger Salamanders (Ambystoma tigrinum) Terrestrial salamanders, typically 15-25 cm in length, with a wide

range across eastern North America from the Gulf Coastal Plain to the

Midwest. A. tigrinum is

characterized by a robust body with four, short well-developed limbs, a broad

head, and a bluntly rounded, broad snout. The tiger salamander is an active

burrower and utilizes burrows as permanent dwellings. Field studies of these

burrows have shown that the burrows may be up to 60 cm below the surface. (Results published in Topics

in Geobiology: Experimental Approaches to

Understanding Fossil Organisms [PDF]) |

|

|

Marbled Salamanders (Ambystoma opacum) Terrestrial salamanders, typically 5-10 cm in length, distributed

across the eastern United States from New England to Florida and as far west

as eastern Texas. A. opacum is

characterized by a small body, short limbs, and a broad head with a blunt

snout. These salamanders spend most of their time in shallow burrows which

are primarily constructed by enlarging holes and cracks already present in

the soil. (Results published in Topics

in Geobiology: Experimental Approaches to

Understanding Fossil Organisms [PDF]) |

|

|

Horned Frog (Ceratophrys cranwelli) A medium-sized (8-13 cm) terrestrial frog endemic to the dry

regions of Argentina. They feed on insects and other animals of similar size.

They normally excavate shallow depressions with their hind legs, but can also

burrow completely below the surface in extreme conditions. At high

temperatures, C. cranwelli

creates a cocoon of skin to trap moisture. |

|

|

Eastern Spadefoot Toad (Scaphiopus holbrooki) A small (4-5 cm) toad endemic to eastern North America. These

toads spend the majority of their lives in deep burrows, coming out to breed during

wet seasons. Spadefoot toads excavate quickly with their hind legs, but move

little sediment up to the surface. The burrows are simple vertical to

subvertical shafts ending in an asymmetrical chamber. (Results published in Palaeontologia Electronica v. 18) |

|

|

Ocellated Sand

Skinks (Chalcides ocellatus) This medium-sized skink (15-30 cm long) inhabits arid

environments from southern Europe, northern Africa, and western Asia. C. ocellatus is a generalist sand

swimmer that is found in sand dunes, gravel plains, and river beds. Sand

skinks burrow by “swimming” through loose sand. While this behavior does not

produce open burrows, it does disrupt primary sedimentary structures and

produces distinctive biogenic structures. (Results published in Palaeontologia Electronica v. 17) |

|

|

Gold Skink (Mabuya multifaciata) Medium-sized, generalist skinks (15-30 cm long) that inhabit a

wide variety of environments. Mabuya

burrow by excavation of the substrate to produce open burrows in sandy soils. (Results published in Topics

in Geobiology: Experimental Approaches to

Understanding Fossil Organisms [PDF]) |

|

|

Field Research |

|

|

In addition to laboratory work, research on burrowing organisms

in their natural environments is critical to interpreting continental trace

fossils. Soils are complex assemblages of biotic and abiotic elements each

capable of masking or potentially highlighting the other. In order to make

accurate paleoecological interpretations based on continental ichnofossils

and paleosols, these modern communities must be studied in the field. My field-based neoichnological research to date has involved

modern soil communities in floodplains and wetlands of eastern Kansas, the

badlands and prairies of northeastern Colorado, as well as the high desert

and mountains of the Sonoran Desert in Arizona. |

|

|

Continental Neoichnology

Database |

|

|

The Continental Neoichnology

Database is a new website that contains the results of the experiments

conducted in the CIRL including basic descriptions of the animals studied,

their behaviors, and the biogenic structures they produced as well as the

detailed qualitative and quantitative data collected from each study.

Photographs, videos, and downloadable files are available for each of the

animals. The database is designed to facilitate the access of neoichnological

information for educators, students, paleontologists and anyone else interested

in learning about terrestrial burrowing animals, their behaviors, and the

traces they produce in a variety of sediments and soils. |

|

|

Copyright © 2007 Daniel Hembree Last revised: 10/2021 |

|